The Demise of Affirmative Action in Higher Education: Where Do We Go From Here?

8.22.2023

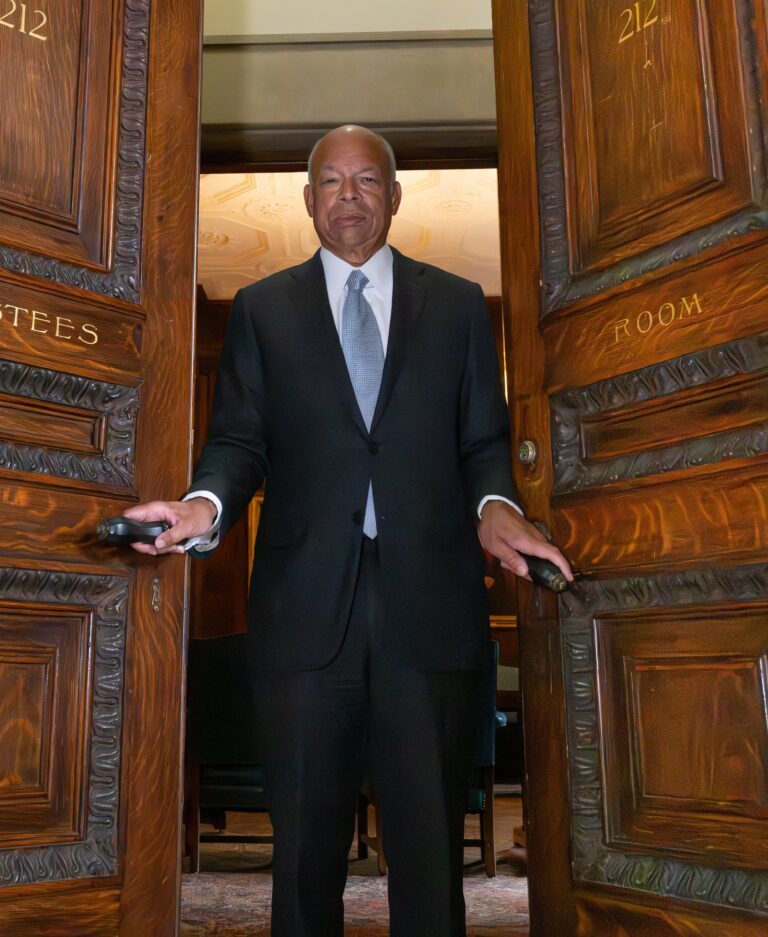

Former Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson poses at the entrance to the Trustees Room at Columbia University. He is a trustee of the university.

Forty-five years ago, I was a summer intern in the Washington office of U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan. For a 20-year-old from Wappingers Falls, New York, the summer on Capitol Hill working in the United States Senate was an extraordinary experience that inspired me toward my own career in law and public service.

That same summer of 1978 I was also a rising senior at Morehouse College, preparing my applications to the top law schools in the country. At the same time, I was nervously awaiting the Supreme Court’s decision in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,[1] the first case to reach the high court that challenged the constitutionality of affirmative action in higher education. Given the timing of the case, I knew then that my own future likely hung in the balance. I still recall the moment, on June 28, 1978, when I learned of the Supreme Court’s decision. A receptionist in Senator Moynihan’s front office knew of my intense interest in the case and sought me out in the mailroom in the basement of the Russell Senate Office Building to tell me the decision was out. But she didn’t know how to characterize the decision’s bottom line for me.

Was affirmative action in higher education in or out? It took me several reads of the court’s six-majority, concurring and dissenting opinions to sort it out. The bottom line of it all, found in Justice Powell’s opinion, was the conclusion that “the attainment of a diverse student body . . . is a constitutionally permissible goal for an institution of higher education.”[2] In other words, affirmative action to achieve diversity in America’s colleges and universities was lawful.[3]

Some months later I was admitted to Columbia Law School. I will never know whether I was admitted to Columbia because of affirmative action; I must assume that I was. I went on to a career in both law and public service. I also went on to become a member of the Board of Trustees of Columbia University. At a recent trustee meeting, I recalled that summer of 1978 to Columbia’s outgoing president Lee Bollinger – the modern-day champion of diversity in higher education.[4] I told Lee were it not for Bakke, I would probably not have been admitted to Columbia Law School and, indeed, would probably not be standing there talking to him at a Columbia trustee meeting.

The Columbia Law School class that entered with me in 1979 and graduated with me in 1982 was exceptionally diverse. Of the 296 in the class, 27 were African American. Many of those Black students went on to join America’s largest corporate law firms. Some became partners. They also included a future cabinet secretary, a future attorney general of the State of New Jersey, and a future New York State Supreme Court justice. One other classmate, Rolando Acosta, became the presiding justice of the Appellate Division, First Department, and thereby became the highest-ranking judge of Dominican descent in New York State history.

The Columbia Law class of 1982 reflected a broader upward trend. By 2009, 11-12% of students at Harvard Law School were Black – roughly the equivalent of the overall Black population in the United States. This diversification in law schools has had a cascading, positive effect on the legal profession. As noted in an American Bar Association study from 2003, “a diverse legal profession is more just, productive and intelligent because diversity, both cognitive and cultural, often leads to better questions, analyses, solutions and processes.”[5]

The judiciary, in particular, now looks more like America. As documented in my own 2020 report on equal justice in the New York State courts, from 1991 to 2020, the percentage of Black judges in New York increased from 6.3% to 14%.[6] In 1991 there was a more than 20-point gap between the percentages of the New York State population that was non-white (30.7%) and state judges who were non-white (8.2%).[7] By 2020, the non-white population of New York State had grown to 44.8%, but the percentage of non-white judges had also grown to 23.9%.[8]

And, of course, since Bakke, numerous Black graduates from the nation’s top law schools have gone on to become cabinet secretaries, deputy secretaries, members of the U.S. House and Senate, a House minority leader, a U.S. attorney general, a U.S. Supreme Court justice, a governor of Massachusetts, a vice president and a president.

Likewise, studies reveal that diversity in the nation’s medical schools has strengthened the medical profession and alleviated racial disparities in the quality of health care. Black and Hispanic medical students are on average more likely to consider treating underserved communities.[9] And a racially diverse care team produces better health outcomes for minority patients due to increased levels of trust and insights into care.[10]

In my own life experience, I have seen the benefits of diversity in the practice of law, in the conduct of foreign affairs and in national security (in both the miliary and among civilians). I have seen firsthand the benefits to my own adult children of diversity in their circumstances growing up, as they interact today with contemporaries of multiple races.

No one should be surprised by the Supreme Court’s decisions in Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina.[11] Given its increasingly conservative membership, the Supreme Court has been headed in this direction for years. Even Chief Justice Roberts, regarded as more moderate among the conservatives, signaled clearly his own animosity toward affirmative action 16 years ago when he declared “[t]he way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”[12] In her 2003 majority opinion in Grutter v. Bollinger upholding the use of race in higher education admissions, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor – the foremost swing vote among modern-day justices – warned that race-conscious admissions policies must be limited in time and that “we expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest approved today.”[13]

The current Supreme Court did not even wait 25 years. The court declared the race-conscious admissions plans at both Harvard and UNC were unconstitutional. The vote in the UNC case was 6-3.[14] Predictably, all six of the Republican appointees voted to reject the plan, and all three of the Democratic appointees voted in favor of it. Presidential elections do have consequences.[15] (Ironically, the Supreme Court that decided this case was also the most diverse in history; no one should doubt that race and gender played a role in those appointments.)

I believe the court’s decision is a setback for America. In the year 2023 it is still the impulse of many in our country to self-segregate – where we live, where we worship and with whom we socialize. For recent generations of American teenagers, higher education has been the first opportunity to broaden their horizons by living, socializing and learning with those different from themselves – whether at Harvard, UNC or Montclair State University in New Jersey. As Justice Powell noted in Bakke, higher education is the opportunity for the “robust exchange of ideas.”[16] As Justice Sotomayor noted in her dissent in the Harvard and UNC cases, with a diverse student body on a college campus, “‘racial stereotypes lose their force’ because diversity allows students to ‘learn there is no “minority viewpoint” but rather a variety of viewpoints among minority students.’”[17]

The court’s decision in the Harvard and UNC cases is now the law of the land. The question now is: where do we go from here?

Immediately after the decision, the current president of the New York State Bar Association, Richard Lewis, appointed me and my two law partners Brad Karp (chair of Paul Weiss) and Loretta Lynch (former U.S. attorney general) to co-chair a task force to study this question. The response to our call for task force members was gratifyingly swift and vast. Within a few short days we recruited over 50 people, including 16 law firm chairs or managing partners, 10 corporate GCs, three law school deans and five members of the state judiciary to join the task force. Most of those who volunteered for the task force are white. As I write this essay, we have begun our work, and our report and recommendation will be issued publicly for comment in short order.

Our task is not to conjure up “workarounds.” We will put forth ideas for a whole new way of promoting and maintaining diversity in higher education and beyond, with the likely incidental benefit of diversity in race.

Speaking for myself, I make the following observations:

First, the court’s decision in the Harvard and UNC cases involved challenges to the admissions programs of two publicly funded universities, under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964[18] and the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. Title VI and the Equal Protection Clause do not apply to most private employers in the absence of federal funding. Thus, the Harvard and UNC cases do not apply explicitly to the private sector. However, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act and other federal and state laws do. Employment law experts predict that the court’s decision – in particular, the concurring opinions of Justices Thomas and Gorsuch – will embolden legal, legislative and activist shareholder challenges to efforts to promote and maintain diversity in the workplace. Those challenges have already begun. On July 13, Republican attorneys general from 13 states sent a joint letter to the CEOs of every Fortune 100 company, reminding them of their “obligations as an employer under federal and state law to refrain from discrimination based on race, whether under the label of ‘diversity, equity and inclusion’ or otherwise.” On July 17 Senator Tom Cotton, a Republican from Arkansas, sent a letter to 51 of the nation’s leading law firms threatening increased use of Congress’ oversight powers with respect to law firms’ DEI programs and even with respect to the legal advice law firms are providing to their clients concerning DEI. Those of us in the private sector must be prepared.

Second, it is important to note the following key passage in Chief Justice Roberts’ majority opinion:

Nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration or otherwise.

Thus, the majority leaves open the possibility that a college or university may consider, as a matter of personal characteristics, the way in which an applicant has faced the challenge of race discrimination in his or her life. This makes sense. On search committees in private life, a frequently asked question of an applicant is, in substance, “tell me about a personal challenge or crisis in your life, and how you dealt with it?” In America today, personal challenges still encompass discrimination on the basis of race.

Jeh Johnson poses with a statue of U.S. District Judge Simon H. Rifkind, who was one of the founders of the law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkin, Wharton & Garrison where Johnson is a partner.

Third, let no one believe that if affirmative action to attain racial diversity is ended, the progress to date will self-perpetuate. To the contrary, experience teaches that if affirmative action in higher education is discontinued, progress to date will wither on the vine.

With the passage of California’s Proposition 209 in 1996 (prohibiting the use of affirmative action in higher education admissions) the University of California system saw a marked decline in the admission of African Americans, Hispanics and American Indians at every campus.[19] At UC Berkeley, the percentage of Black students in the freshman class dropped from 6.32% in 1995 to 3.37% in 1998. [20] Admissions for Latinos dropped from 15.57% to 7.28% in the same period, though Latinos made up 31% of California public high school graduates.[21]

Likewise, in Texas immediately following the 1996 decision of the Fifth Circuit in Hopwood v. State of Texas,[22] the admission of Black students at the University of Texas School of Law fell 90%, from 38 to four students.[23] Similar downward plunges in diversity occurred in Oklahoma’s colleges and universities following the passage of a state constitutional amendment banning affirmative action there in 2012[24] and in Michigan with the passage of Proposition Two there in 2006.[25]

There is every reason to believe that corresponding backslides in diversity will occur in the professions that depend on a diverse pipeline of graduates from higher education. As Justice Sotomayor noted in her dissent, eliminating affirmative action in higher education will cause a return to “a leadership pipeline that is less diverse than our increasingly diverse society, reserving ‘positions of influence, affluence, and prestige in America’ for a predominantly white pool of college graduates.”[26]

If, then, all considerations of race are to be banned from our thinking when it comes to efforts at achieving diversity, we must pursue other efforts that will likely have the incidental effect of promoting diversity by race.

Throughout her eloquent dissent, Justice Sotomayor noted that racial disparities in America are “interlocked” with residential segregation, poverty, substandard schools and other systemic inequities. These parallels are viewed from the starting point of race. The majority opinion would seem to now require and permit that we view these “interlocked” factors through the flipside of the lens, looking first to the other systemic inequities.

For example, in the wake of the Hopwood decision, in 1997 the Texas Legislature enacted the “Top 10 Percent Law,” which guarantees that all students who graduate in the top 10% of their high school classes are accepted to state-funded universities, ensuring geographic, cultural and socioeconomic diversity drawn from across the state. Though there is a debate about the data, the policy appears to have had the incidental impact of promoting racial diversity in the Texas system given the existing racial segregation in Texas public high schools.[27] Nationwide, many colleges and universities across America seek to achieve geographic, cultural and socioeconomic diversity, which ought to have the impact of promoting racial diversity as well.

Of course, there is a cautionary note here. Courts have considered facially race-neutral policies and practices with a disparate, discriminatory impact to be illegal as well. The leading Supreme Court case in this area is Griggs v. Duke Power Co.[28] Griggs involved a 1960s-era policy at Duke Power in North Carolina of administering aptitude tests to non-high school graduates as a means to promotion. The policy had a vastly disparate impact of favoring whites over Blacks. The court held the policy violated Title VII for that reason.

The logic of Griggs should not be taken too far. For example, should that same logic prevent affordable flood insurance to vulnerable neighborhoods in New Orleans, because it would have a favorable impact on Black homeowners in those neighborhoods? Or does the logic of Griggs prevent the New York City Police Department from sending enhanced public safety resources to high-crime precincts, because it will disproportionately benefit Black inhabitants of those precincts? In both cases, such a result would be absurd. Critically, in Griggs, the court noted the legacy of inferior Black education in North Carolina as a root cause of the disparate impact.[29]

The bottom line is this: In the quest and zest for a constitution that is unqualifiedly “colorblind,” we cannot close our eyes to the America in which we live. In principle, a “colorblind” constitution is a noble cause. In reality, it is reminiscent of the fallacy that “separate can be equal.” In 2023, systemic inequities in American wealth, geography, home ownership, education and health care remain, and they remain “interlocked” with race. Diversity in higher education is the pipeline to a better, smarter America. In the pursuit of a more perfect union, race-neutral efforts to achieve student bodies that look like America must continue.

Jeh Johnson at Columbia University. He graduated from Columbia Law School and is a university trustee.

Jeh Charles Johnson is partner at Paul Weiss Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. He was secretary of Homeland Security (2013–2017); general counsel of the Department of Defense (2009–2012); general counsel of the Department of the Air Force (1998–2001); assistant U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York (1989–1991) and is a trustee of Columbia University.

[1] 438 U.S. 265 (1978).

[2] Id. at 311-12.

[3] See also Fisher v. Univ. of Texas at Austin, 570 U.S. 297 (2013); Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003).

[4] See Grutter, 539 U.S. 306.

[5] Diversity in the Law: Who Cares?, American Bar Association, April 30, 2016, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/litigation/committees/diversity-inclusion/articles/2016/spring2016-0416-diversity-in-law-who-cares.

[6] Report from the Special Adviser on Equal Justice in the New York State Courts, Oct. 1, 2020, at 33.

[7] Id. at 32.

[8] Id.

[9] Douglas Grbic & Franc Slapar, Changes in Medical Student’s Intentions to Serve the Underserved: Matriculation to Graduation, 9 Analysis in Brief No. 8 at 2 (AAMC July 2010).

[10] See Brief for Amici Curie Association of American Medical Colleges et al. in Support of Respondents, filed in the Harvard and UNC cases on July 28, 2022, at 11-12.

[11] 600 U.S. ____ (2023).

[12] Parents Involved in Cmty. Sch. v. Seattle Sch. Dist. No. 1, 551 U.S. 701, 748 (2007) (plurality opinion).

[13] 539 U.S 306, 343 (2003).

[14] The vote in the Harvard case was 6-2 as Justice Jackson recused herself from that decision.

[15] Likewise, in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Org., 597 U.S. ___ (2022), the decision of the court to overturn abortion rights first declared in Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973), the six justices who voted in the majority were all Republican appointees and the three dissenters were each Democratic appointees.

[16] Regents of Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 313 (1978).

[17] Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. Presidents and Fellows of Harvard Coll., 600 U.S. __ (2023) (quoting Grutter, 539 U.S. at 3119–20).

[18] 78 Stat. 252, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d et seq.

[19] See Brief of the Washington Bar Association and the Women’s Bar Association of the District of Columbia as Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondent filed in the Harvard and UNC cases on August 1, 2022, at 24.

[20] Students for Far Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. University of North Carolina, 600 U.S. ___ (2023) (Sotomayor, J., dissenting).

[21] Id.

[22] 78 F.3d 932 (5th Cir. 1996).

[23] See Brief of the Washington Bar Association and the Women’s Bar Association of the District of Columbia as Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondent filed in the Harvard and UNC cases on August 1, 2022, at 24–25.

[24] Id. at 25.

[25] See Brief of Amici Curiae National Black Law Students Association in Support of Respondents filed on August 1, 2022, in the Harvard and UNC cases, at 27.

[26] Citing Regents of Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 401 (1978) (Marshall, J., concurring).

[27] Kate McGee, With Race-Based Admissions No Longer an Option, States May Imitate Texas Top 10% Plan, Texas Tribune, June 29, 2023, https://www.texastribune.org/2023/06/29/texas-college-top-ten-percent-plan-supreme-court.

[28] 401 U.S. 424 (1971).

[29] Id. at 431.