Terrorists Use Atrocities To Unravel Communities and Make Recovery Difficult

1.16.2025

The atrocities of war and armed conflict are often brutal, ranging from terror to rape and murder. For survivors, the trauma doesn’t end when the war ends, especially if their trauma is not addressed and they are not able to return to normal life.

Such is the case for the survivors of the Yazidi genocide in Iraq and the Oct. 7 attacks on Israel. Israel and Hamas have a ceasefire in place, albeit a precarious one, yet thousands of Yazidi women kidnapped by ISIS and taken as sex slaves have yet to return home.

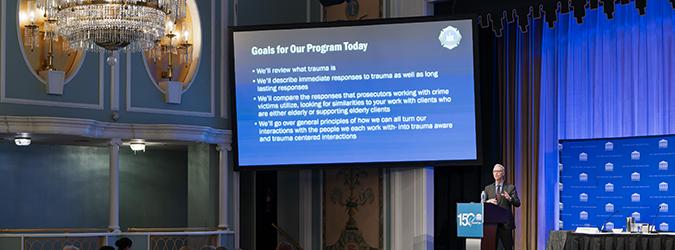

The New York State Bar Association hosted a Presidential Summit of international human rights experts, as part of its Annual Meeting in New York City, to tackle issues of how victims of war can find recovery and justice.

The panelists were:

- Cochav Elkayam-Levy, international human rights law expert, Israel Prize winner, and founder and chair of the Civil Commission on October 7th Crimes by Hamas Against Women and Children.

- Susana SáCouto, director of the War Crimes Research Office of the American University Washington College of Law, which promotes the development and enforcement of international criminal law and international humanitarian law.

- Abid Shamdeen, advocate for Yazidi genocide survivors and co-founder of Nadia’s Initiative, a nonprofit organization committed to both rebuilding communities in crisis and advocating for justice for survivors of sexual violence on a global scale.

Susan L. Harper, treasurer of the New York State Bar Association and the founder of the association’s Women in Law Section, moderated the discussion.

The Lasting Effects of Conflict-Related Sexual Violence

The United Nations states that conflict-related sexual violence refers to rape, sexual slavery, forced prostitution, forced pregnancy, forced abortion, enforced sterilization, forced marriage and any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity perpetrated against women, men, girls or boys that is directly or indirectly linked to a conflict. The perpetrator may be affiliated with a state or non-state armed group, which includes terrorist entities.

“The bottom line is that [conflict-related sexual violence] is a violation of human rights and humanitarian law, and a crime under international law,” said SáCouto. “It can and often does have devastating consequences on individuals, families, and communities. Survivors experience physical and psychological trauma, often social stigma… The widespread occurrence of [conflict-related sexual violence] often triggers displacement of the victims and tears at the social fabric of communities.”

SáCouto added that conflict-related sexual violence also creates widespread intergenerational trauma – including children born of rape – while the ensuing distrust makes peace negotiations and reconciliation efforts more difficult.

“ISIS used the rape and enslavement of Yazidi women as a weapon against our community,” said Shamdeen. “To destroy our community from within… Many of these women I know personally were taken into sexual slavery. Many of them died during the war.”

Shamdeen added that while Nadia’s Initiative has helped rebuild communities, half of the survivors have not been able to return home to the Sinjar region of Iraq. Although it has been 10 years since the Yazidi genocide started on Aug.3, 2014, there are still 200,000 people living in refugee camps.

“The aftermath of this genocide weighs on the Yazidi community even more than the genocide itself,” he said. “You have this prolonged displacement inside your own country. Imagine putting the entire population of the Los Angeles fires in a tent camp for 10 years a few hours away from LA, and saying ‘just live in these camps for 10 years until the conditions are perfect.’ And that’s what’s happening.”

Naming and Identifying Kinocide

In documenting the attacks on Oct. 7, Elkayam-Levy and her team found a disturbing pattern – Hamas deliberately targeted families. They are calling this weaponization of the family unit kinocide.

“If there is hell this is what it looks like,” said Elkayam-Levy. “Someone abusing your kids. Someone abusing your loved ones. It’s one thing to hurt a child. It’s another thing to do it in front of their parents or siblings.”

And Hamas spread the terror by using the social media accounts of their victims.

In one horrific example, terrorists murdered Maayan Idan in front of her parents and younger siblings – and then broadcasted the family’s anguish on Facebook Live. Maayan had just celebrated her 18th birthday, and balloons were still floating in their house.

The terrorists then took her father, Tsahi Idan, hostage. He was killed in captivity. His body was returned to Israel in February as part of the ceasefire agreement.

Hamas is still holding 59 people hostage.

Finding Justice

The panelists agreed that while justice can take many forms, it often takes years – or even decades. And that’s even if it happens. But for victims, being able to name and recognize what happened to them helps.

“I think the most important part of this work is that we gave language to describe the suffering of these people,” said Elkayam-Levy. “We met victims from all around the world… and seeing in their eyes that we recognized what happened to them – they told us ‘This happened to us, this happened to our families.’ It meant the world to be able to [name] what they had been through.”