The Birth of the New York State Bar Association

4.13.2022

1876 was an eventful year. The Centennial of American Independence was celebrated. Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone and the Brooklyn Bridge was under construction. Mark Twain’s inventor, Samuel L. Clemens, published “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.” And the Battle of Little Big Horn, where George Armstrong Custer made his “Last Stand,” was fought in the Montana territory.[1]

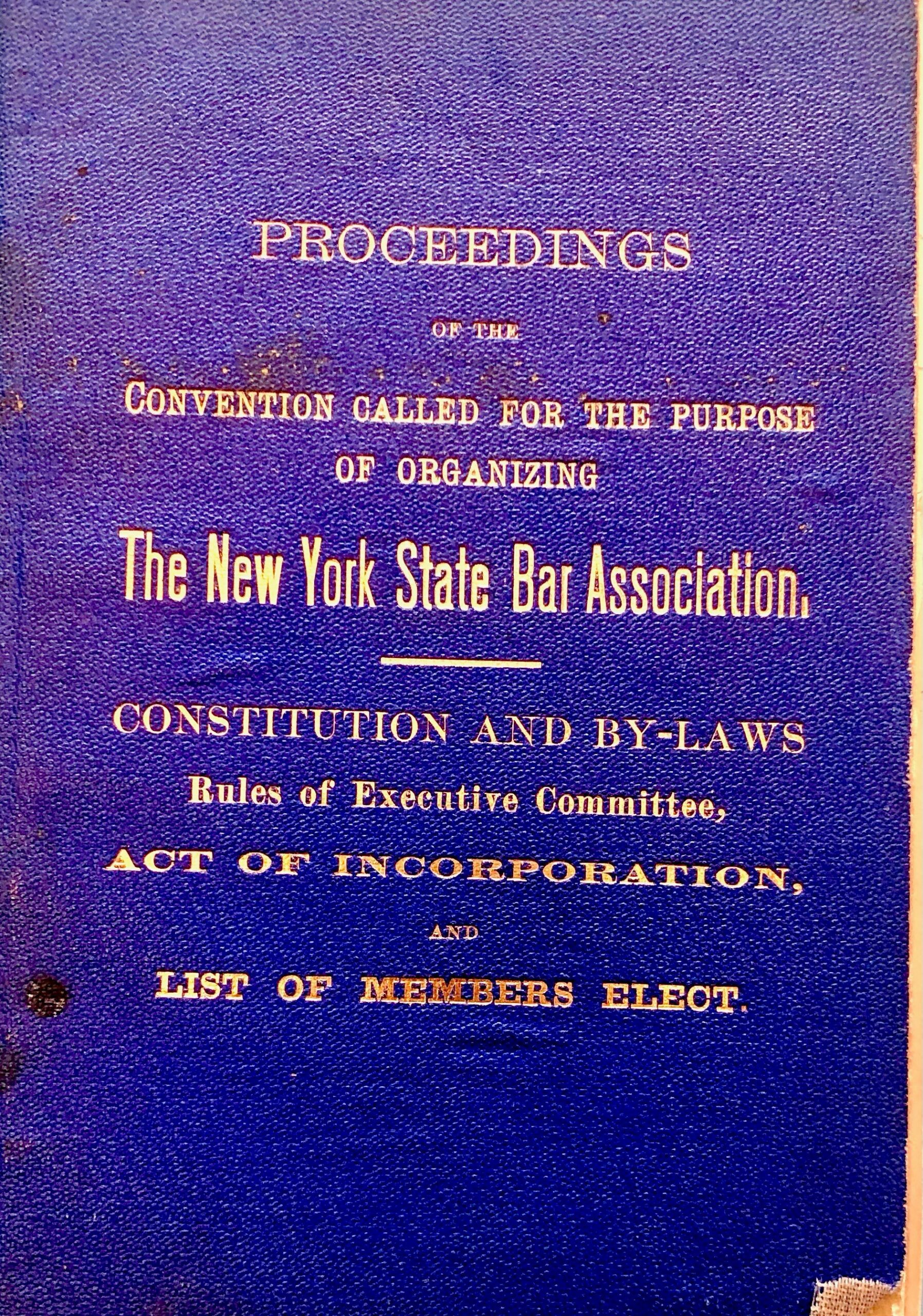

1876 was a historic year for the legal profession, too. On a late November afternoon, the New York State Bar Association was born. Bar associations existed before then, but most served mainly social purposes.[2] While lawyers had previously joined together on a statewide basis, those efforts did not produce durable organizations.[3] The Association was the nation’s first state bar capable of legislative advocacy, developing public policy proposals and continuing legal education. It remains the oldest and largest voluntary state bar association in continuous existence.

The Call for a Statewide Bar Association

The apparent impetus for the Association’s formation was a story appearing in the Albany Law Journal, which had the largest circulation of any legal periodical of its time.[4] On the front page of the June 26, 1875 issue, the Journal called for the establishment of a state bar in New York.[5] In 1870, when the Association of the Bar of the City of New York was formed,[6] the prospect existed that, through its efforts, other local bar associations, and ultimately a state bar, would be organized.[7] But the City Bar had not taken the initiative. The Journal’s editor, Isaac Grant Thompson, believed that lawyers of the state should be “combined in an organic whole,”[8] which, as a collective force, could “do much in directing legislation on matters of jurisprudence, in improving the law and in advancing the best interests of the profession.”[9]

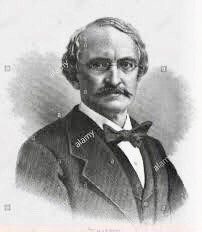

Elliott Fitch Shepard answered the Journal’s call to action.[10] Shepard was a public-spirited lawyer and pillar of the community in New York City.[11] Mildly eccentric and immensely wealthy, he represented the New York Central Railroad and several other large corporations but devoted his later years to editing a newspaper he owned, the Mail and Express. He was tall and dignified, with a pleasant expression and manner, and addressed as “Colonel,” the rank to which he rose in the Union Army during the Civil War.[12] No single person founded the Association. But no one did more than Shepard to make it happen.[13]

On Oct. 12, 1875, Shepard introduced a resolution at a City Bar meeting to appoint a committee “to investigate and report upon the feasibility and desirability of taking initiatory steps toward organizing an Association of the Bar of the State of New York.”[14] The City Bar adopted the resolution, and Shepard was appointed chair of a five-person committee.[15]

Shepard and his colleagues leapt to action.[16] First, the committee surveyed lawyers throughout the state on their views about creating a state bar. A letter containing 16 questions was sent to 1,300 lawyers, approximately one-half of whom practiced outside New York County. There were then an estimated 6,000 to 7,000 lawyers in the state (approximately the same number of physicians).[17]

The committee’s first question was: “Do you favor generally the formation of a State Bar Association?” The response – 306 to 4 in favor – was a nearly unanimous vote of approval. In response to another question, 239 lawyers named Albany as the proper place for permanent headquarters, and 21 named New York City. A variety of answers were given to questions about admission fees, dues and meetings. The question generating the sharpest difference of opinion was whether members should be selected by local bar associations or whether all members of the profession should be able to join irrespective of their connection to a local bar. Sixty-four answered that local bars should select members, while 187 indicated that lawyers should be eligible even if local bars did not choose them. Finally, 253 lawyers said they would join a state bar if one were formed.[18]

In December 1875, the Shepard Committee issued a report recommending that the City Bar “take initiatory steps toward the formation of a State Association.”[19] The report cited the example of England’s Inner and Middle Temple, and Lincoln’s and Grey’s Inns, as voluntary organizations that contributed to “the high character of the English Bar.”[20] The committee did not opine on how members should be selected, leaving that question to the future organization to settle when constituted.[21] It did, however, maintain that a state bar would result in the improvement and elevation of lawyers, by giving them an opportunity to “be heard on the higher topics of the rights of persons, the administration of government, the security of property, the philosophy of jurisprudence, the history of the law, the suggestions of progress, the victories of reform.”[22]

To organize and establish a state bar, the committee recommended holding a “convention”[23] composed of delegates from New York’s eight judicial districts (as then constituted).[24] The proposed plan was for the City Bar to invite each judicial district to select 20 delegates and 20 alternates for the convention. About 100 lawyers were expected to attend the convention, giving it a representative character.[25]

On the evening of Dec. 14, the Shepard Committee report was presented at a meeting of the City Bar held at its headquarters on 7 West 29th St.[26] Many prominent members attended the meeting, chaired by the City Bar’s president, William M. Evarts, a former U.S. attorney general and future U.S. secretary of state and U.S. senator.[27] The members voted to adopt the committee’s report, but tabled a resolution implementing its recommendations until the City Bar’s next meeting.[28] That occurred on April 11, 1876, when Shepard moved for adoption of the resolution. The motion carried and Shepard’s Committee was tasked with organizing the convention.[29]

As word spread about the convention, so too did support for establishing a state bar.[30] The New York Times reported that “[t]he project for the formation of the State Association seem[ed] to have taken deep root among the members of the legal profession,”[31] and had “the endorsement of all the leading Judges and lawyers of the State.”[32] In March 1876, the Times inked an editorial arguing that a state bar was necessary to remedy “many irregularities and evils” that “can never be amended except by a unified effort among the better members of the profession.” A state bar could, for example, “rais[e] the standard of admission to the profession” and to stem the “flooding” of “half prepared young lawyers . . . which has prevailed for the last few years,” the Times observed.[33]

Organizing the Convention

The Shepard Committee set to work organizing the convention. In addition to inviting judicial districts to appoint their representatives, the committee had to choose a place and time for the convention, prepare an agenda, recruit leaders, devise a committee structure and draft foundational documents.[34]

The judicial districts promptly responded to their invitations. On May 30, lawyers in the 3rd Judicial District convened in Albany to select delegates and alternates.[35] Over the summer, meetings were held by the 1st Judicial District in New York City,[36] the 2nd Judicial District in Brooklyn[37] and the 5th Judicial District in Syracuse.[38] The other judicial districts did likewise.

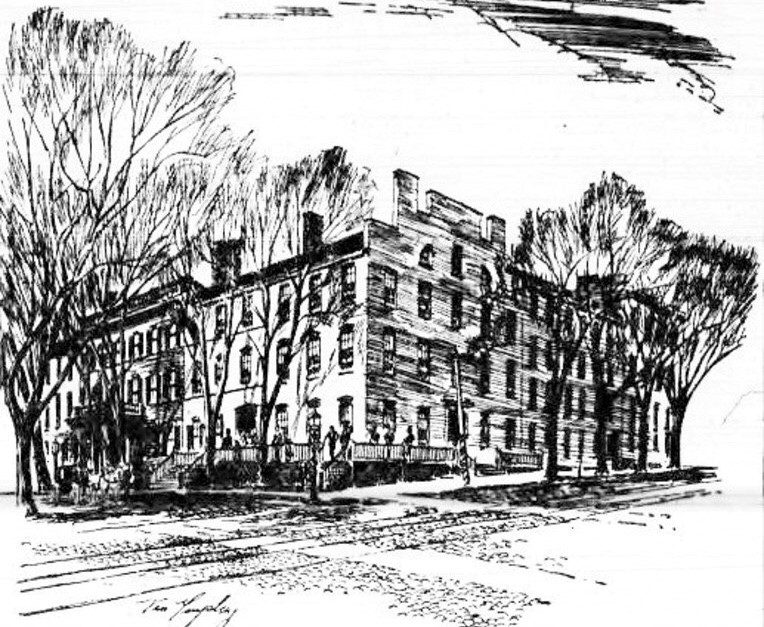

The convention was scheduled for Nov. 21 in Albany, in the old state Capitol. Designed by noted architect Philip Hooker and completed in 1809 with a three-story portico, it was an impressive venue.[39]

As the convention drew near, America was in turmoil over the presidential election on Nov. 7 between New York Governor Samuel J. Tilden and Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes.[40] Tilden won the popular vote by a decisive margin. But Hayes’ allies challenged the returns in four states that would determine the majority vote of the electoral college. Congress appointed an electoral commission which, by a single vote, gave the election to Hayes. The final electoral college tally of 185 to 184 came only a few days before Hayes’ scheduled inaugural in 1877.[41]

The Association Is Formed

Ninety-one delegates assembled in the Assembly Chamber of the venerable old Capitol on Nov. 21, 1876.[42] “[S]eldom,” it was remarked, “had there gathered together so many leading members of the Bench and Bar.”[43] The delegates came from every region.[44] The Times described them as representing, “in an unusual degree, the learning and culture of the Bar of the State.”[45]

Shepard called the meeting to order at 3:30 p.m. and moved that William C. Ruger from Syracuse serve as temporary chairman.[46] Ruger was the first president of the Onondaga County Bar Association (founded the year before) and “one of the strongest and best equipped lawyers” in the state.[47] In 1882, he became the Association’s fourth president, and was elected later that year to chief judge of the Court of Appeals.[48] One newspaper endorsement of his candidacy posed the rhetorical question: “Thus standing the recognized head of the bar of the State of New York, who is more fit to sit at the head of the highest court of the state?”[49]

Upon taking the chair, Ruger briefly addressed the convention, and the roll of delegates and alternates was called.[50] Someone suggested a committee be appointed to propose a resolution forming the Association. But that was unnecessary; the delegates were ready to vote. Thus, a motion was made and carried that it was “expedient . . . a State Bar Association be now formed.”[51] Eight delegates, representing each of the judicial districts, were then selected as vice presidents of the convention, along with three secretaries.[52]

Clifford A. Hand, a founding member of the City Bar,[53] moved that a committee be formed to draft a constitution and bylaws.[54] Debate ensued as to the size of the committee, with some wanting every county in the state represented.[55] Horatio Ballard, a prominent Cortland County lawyer and former New York secretary of state, strongly supported Hand’s motion, which was approved, and a 16-person committee formed, composed of two delegates from each judicial district.[56] The delegates discussed the manner of conducting further business and, without coming to closure, the convention adjourned until the evening.[57]

The convention reconvened at 7:30 p.m., with a larger attendance than in the afternoon.[58] Shepard, on behalf of the Committee on Constitution and Bylaws, reported a draft constitution, which was read out loud by Rockland County Judge Andrew E. Suffern.[59] The delegates went through the draft article by article and, after amending 12 of 22 articles, adopted it.[60]

The constitution provided that any lawyer in good standing, admitted to practice in the state for three years, was eligible for membership.[61] All Court of Appeals and federal judges in New York, as well as state Supreme Court justices, would be honorary members.[62] Annual elections would be held for president, treasurer, recording secretary, corresponding secretary and vice presidents from each judicial district.[63] The Association would be managed by an Executive Committee consisting of three members from each judicial district.[64] Five standing committees were established: Admissions, Grievances, Law Reform, Prizes, and Legal Biography.[65] An annual meeting would be held in Albany on the third Tuesday of November,[66] and an admission fee of $5 was established, with yearly dues of $5.[67] (dues remained at that level until 1928, when they rose to $6.[68]).

The Nominating Committee proposed the following slate of officers:

- President, John K. Porter

- Treasurer, Rufus W. Peckham

- Recording Secretary, Abraham Van Dyck De Witt

- Corresponding Secretary, Edward Mitchell

- Vice President, First District, Charles W. Sandford

- Vice President, Second District, John J. Armstrong

- Vice President, Third District, Samuel Hand

- Vice President, Fourth District, Platt Potter

- Vice President, Fifth District, William C. Ruger

- Vice President, Sixth District, Horatio Ballard

- Vice President, Seventh District, James L. Angle

- Vice President, Eighth District, Myron H. Peck[69]

This was a legal dream team in 1876. As for the officers, Porter was “one of the greatest American advocates”[70] and a former judge of the Court of Appeals.[71] He was involved in many of the famous cases of the day, including the prosecution of Charles J. Guiteau, who assassinated President James J. Garfield in 1881.[72] The Albany Law Journal observed that Porter “comes nearer to being a genius than any other man at our bar.”[73] Peckham, the son of a deceased Court of Appeals judge, later held a seat on that court as well as the U.S. Supreme Court.[74] De Witt was a prominent lawyer and civic leader in Albany.[75] Mitchell, the treasurer of the City Bar, “was a leading lawyer of his time,”[76] later serving as an assemblyman, New York City parks commissioner and U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York.[77]

The pedigrees of the vice presidents were equally dazzling. Samuel Hand (the father of Learned Hand, a legendary jurist of the 20th century) was a former judge of the Court of Appeals,[78] and Ruger a future chief judge.[79] Sandford was a Civil War Union general;[80] Angle, a Supreme Court justice from Rochester;[81] Armstrong, a Queens County judge;[82] Ballard, a former statewide elected official, assemblyman and district attorney;[83] Potter, an ex officio judge of the Court of Appeals,[84] Supreme Court justice and legal scholar;[85] and Peck, one of the ablest attorneys in Genesee County.[86]

The convention elected the officers’ slate, in addition to an Executive Committee and the chairs and members of the other standing committees.[87] Shepard chaired the Committee on Prizes; the other chairs were Peter S. Danforth, a Supreme Court justice from Schoharie County (Admissions);[88] John F. Seymour, a prominent lawyer from Utica whose brother, Horatio, was a former New York governor (Grievances);[89] Matthew Hale, one of Albany’s “foremost lawyers” (Law Reform);[90] and Abraham X. Parker, a former member of the state Assembly and Senate and future congressman (Legal Biography).[91]

The convention had done everything necessary to form the Association. Ruger, as convention president, retired, and the convention permanently adjourned so that the newly formed Association could assemble with President Porter in the chair. Porter immediately convened the Association’s first meeting, with the officers taking their seats.[92]

Greeted with applause, the 58-year-old Porter, bespectacled and mustachioed with a theatrical speaking style,[93] delivered a “particularly happy” address.[94] He thanked the members for their expression of confidence and said that the honor of serving as president was beyond anything that could be bestowed by executive favor or the suffrage of the people. He paid tribute to the nation’s lawyers and predicted a useful future for the Association.[95]

A few remaining issues were addressed. The Executive Committee was directed to take the necessary steps to incorporate the Association.[96] An offer by the Albany Law Journal to act as the Association’s official publication was referred to the Executive Committee.[97] Shepard proposed an annual writing prize on behalf of 25 lawyers from the 1st Judicial District.[98] That offer was accepted, making it the first action taken by the Association apart from matters of formal organization.

The meeting concluded just before 1 a.m.[99] The delegates had “laid down an historic record.”[100]

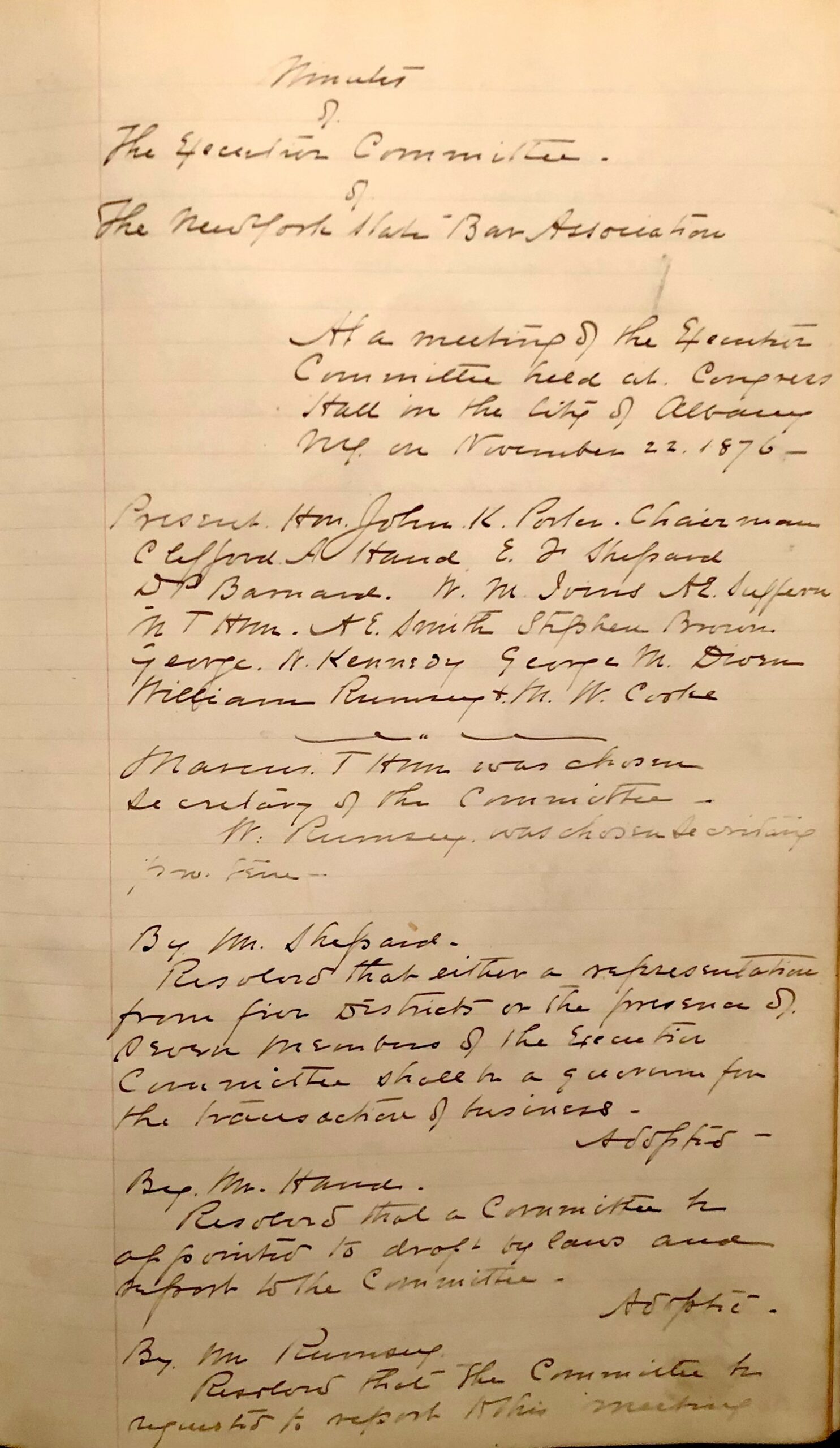

There being no rest for the weary, the Executive Committee, with Porter as its chair, convened later that morning at Congress Hall Hotel, adjacent to the old Capitol. The Executive Committee appointed a subcommittee to draft rules and regulations, fixed the quorum requirement for its future meetings, adopted the Association’s bylaws, and appointed the Albany Law Journal the official publication of the Association.[101] A subcommittee was appointed to draft and lobby for legislation incorporating the Association.[102]

The First Year

The Association’s first year was devoted to organizational matters, with the Executive Committee doing most of the work.[103] In 1877, the Executive Committee met in person five times[104] and transacted most business by correspondence.[105] At its Jan. 13, 1877 meeting, the Executive Committee adopted rules and regulations for itself,[106] amended the bylaws[107] and authorized Porter to designate people to call the first meetings of standing committees.[108] It also selected a new chair for the Grievance Committee, Hamilton Fish Jr. (a future speaker of the state Assembly and congressman), and appointed Chauncey M. Depew (general counsel for the New York Central Railroad and a future U.S. senator) to the Committee on Prizes.[109]

On May 2, the Legislature passed Chapter 210 of the Laws of 1877, entitled “An Act to Incorporate the New York State Bar Association.”[110] It transformed the voluntary Association established at the convention into a body corporate. Section 1 recited that the Association was “formed to cultivate the science of jurisprudence, to promote reform in the law, to facilitate the administration of justice, to elevate the standard of integrity, honor and courtesy in the profession, and to cherish the spirit of brotherhood among the members thereof.”[111]

The act’s reference to “brotherhood” was drawn from the Association’s constitution[112] and reflected the reality that the law was an all-male profession. Women were then barred from practicing law in New York. In 1886, Governor David B. Hill (who, at the time, was also the Association’s president)[113] signed legislation removing restrictions on the admission of women.[114] But it took the Association another 15 years to admit its first woman member and a century to elect a woman president.[115]

The Executive Committee’s July 18 meeting was especially productive. Members convened at the United States Hotel in Saratoga Springs (then the most luxurious resort town in the U.S.) and worked through an agenda dominated by proposals from Shepard.[116] The chairs of the Committees on Admissions and Prizes delivered reports.[117] Also, planning began for the upcoming “annual meeting,”[118] at which substantive reports would be delivered by the Grievance Committee on the unauthorized practice of law,[119] and the Committee on Law Reform on a Code of Civil Procedure being considered by the Legislature.[120]

Like any fledging membership organization, the Association sought to attract dues-paying members.[121] At first, the results were disappointing. On Dec. 15, 1876, Treasurer Peckham mailed a letter to 160 officers and committee members appointed at the convention, advising that they could accept membership simply by paying the “$5 admission fee now, and the $5 annual dues for 1877, any time before May 1st, 1877.”[122] But only 20 people responded in the first few months.[123] By April 1877, the situation was not much improved.[124]

One obstacle was the labyrinthine process for electing members prescribed by the bylaws as well as regulations established by a 32-member Committee on Admissions.[125] To become a member, a lawyer needed to be “admitted” as if to a private club.[126] A candidate had to be nominated by at least one member residing in the same judicial district as the candidate. A committee of members in that district would examine the candidate’s credentials. Only if the district committee unanimously approved the candidate could his name be forwarded to the Executive Committee for approval.[127]

This process perplexed many[128] and was criticized by the Albany Law Journal, which argued that “[e]very member of the bar in good standing should be entitled to admission.”[129] In a stinging editorial, the Journal wrote: “We have read the bylaws of the Association several times over and have dwelt with peculiar interest upon that relating to admission, and yet we are no more able to tell, off-hand, how to get into the Association than Ali Baba was to tell how to get out of the robbers’ cave.”[130]

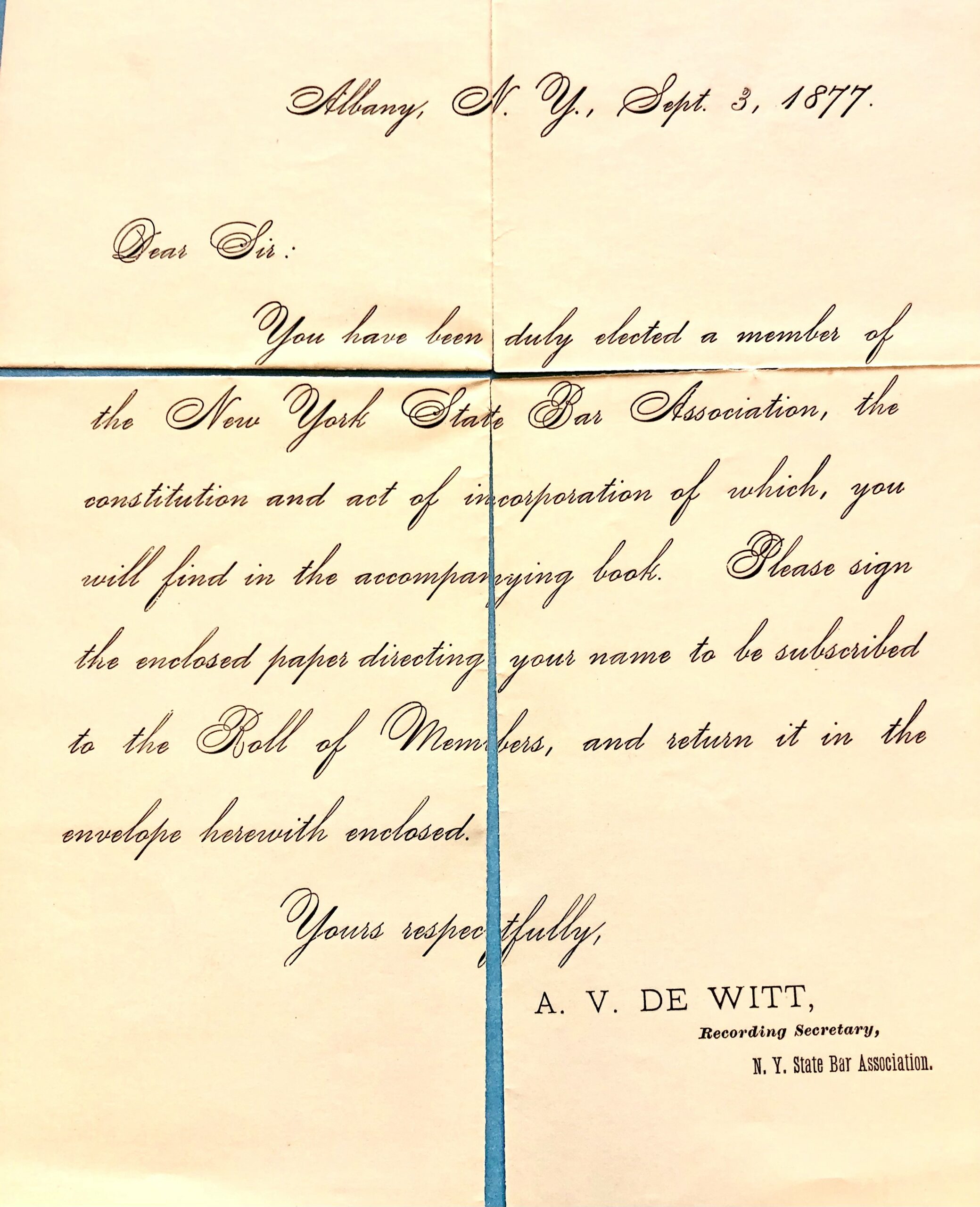

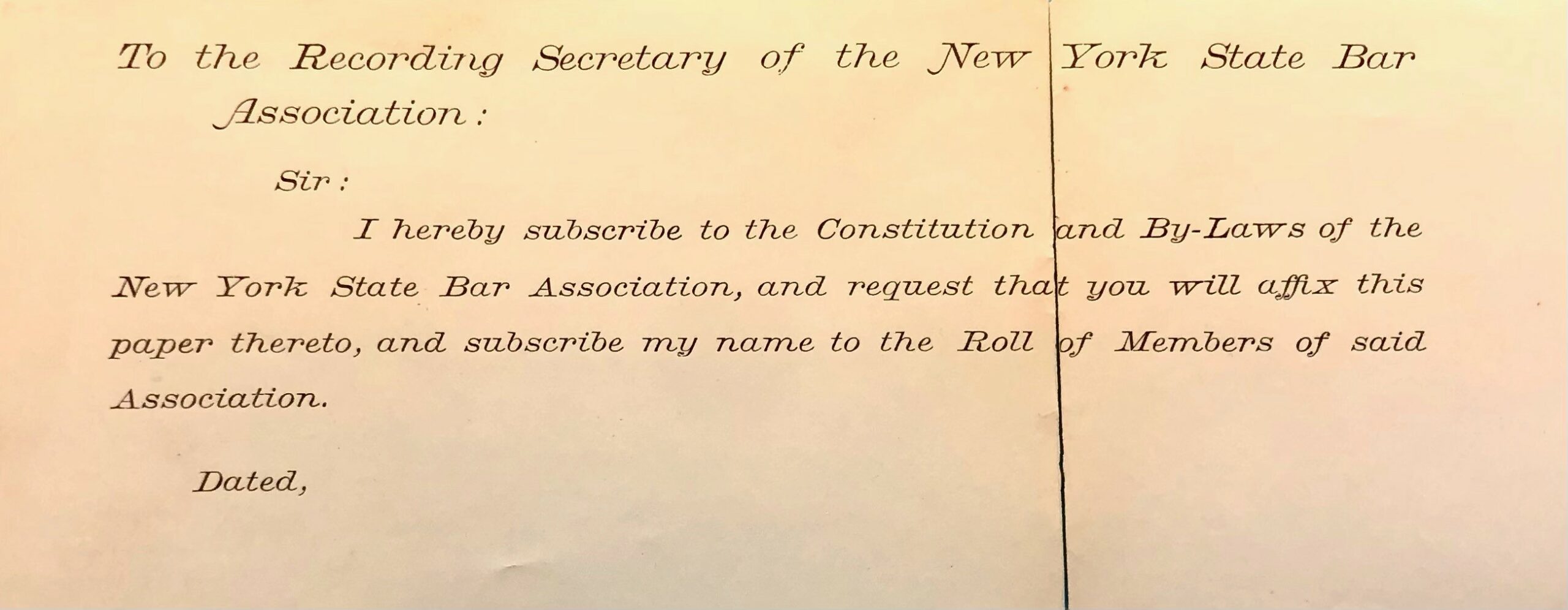

To streamline the admissions process, the Executive Committee eliminated an “obstructive regulation”[131] and mailed to over 1,000 “members elect” a “Blue Book” containing a list of their names as well as the proceedings of the organizing convention, and the texts of the constitution, bylaws, and Executive Committee rules and regulations.[132] Accompanying the Blue Book was a letter informing recipients of their election to the Association and a document to be completed and returned that would secure placement on the Roll of Members.[133]

These efforts bore fruit. In the fall, there was a surge of new members.[134] By November, 356 members paid the $5 admission fee, with many also paying their annual $5 dues.[135] The Association “began its work with a large and distinguished charter membership.”[136]

The First Annual Meeting

The Association’s first Annual Meeting took place on the afternoon of Nov. 20, 1877, once again in the Assembly Chamber of the old Capitol.[137] It was the largest meeting of New York lawyers ever held.[138]

Following an invocation, President Porter delivered an address on the Association’s common purposes and aims.[139] A person who heard it reminisced 20 years later: “No one who was present when President Porter first called the Association to order will forget the thrill awakened by his address.”[140]

Repeatedly interrupted by applause, Porter said the Association was designed for “noble ends” – to be “of practical benefit” to the profession and public.[141] He challenged the members to rise to the occasion:

“Do we, in our day and generation, owe any duty to the profession and to the state? . . . Is it not our duty to add to the effective forces of the state in all the agencies of human progress and improvement? Is it not in our power to exercise a healthful influence upon each other? . . . The influence of our profession in the next generation depends on a large degree on the manner in which we fulfill our duty.”[142]

Porter believed that lawyers could only meet the challenges facing the profession by working together:

“We are strengthened by association with each other. The standard of professional integrity and honor is elevated by mutual intercourse, and by the consciousness that our own status is determined by the enlightened judgment of our brethren. The weight of the profession in the community and its influence upon public affairs are greatly increased when it is known that the ends that they aim to promote are not those of personal ambition, or individual rivalry, but such as are identified with the general good, the advancement of the highest interest of society, the perfecting of our system of jurisprudence, the maintenance of public order and the stability of private rights.”[143]

Porter stressed that the Association’s obligation to the profession and public “reached far beyond the present generation.” He envisioned a day when future generations would remember the founders of “an institution identified with the development of jurisprudence and with the permanent interests and prosperity of the state.”[144] “Let us trust,” he said, “that this Association may endure, and that it may exercise a collective and permanent influence.”[145]

After Porter’s address, the meeting turned to the election of new honorary members. Motions were unanimously approved to elect the chief justice and associate justices of the U.S. Supreme Court, other judges, and the vice president of the United States, William A. Wheeler, a New York lawyer. Perhaps still smarting over New York Governor Tilden’s defeat the year before, a motion to elect President Hayes, members of his cabinet and others was referred to the Committee on Admissions.[146]

Treasurer Peckham reported that the Association’s receipts totaled $3,355.70, and disbursements were $1,500, leaving a balance of $1,855.70.[147] Chairs of the standing committees delivered reports,[148] and papers were read on domestic relations law[149] and proposed changes in probate procedure.[150]

Loud applause greeted the appearance of the chief judge of the Court of Appeals, Sanford E. Church.[151] His assignment was to present the Post-Graduate Prize to Walter R. Howe, the 27-year-old author of the winning essay, “The Legal Relations of Capital and Labor.” This was a controversial subject selected for contestants by the Committee on Prizes.[152]

It was the Gilded Age: an era of rapid economic expansion, accompanied by labor strife, income disparity and political agitation.[153] Shepard, the committee’s chair, was “one of the major conservatives of his day.”[154] He opposed strikes, believing that the modern corporation was “one of the greatest blessings of the nineteenth century, and a distinguishing mark of its civilization.”[155] In his committee report, he said that “if the result of the presentation of this topic should be a calm, learned, comprehensive and judicious treatise, recalling the attention of the people to the legal principles which underlie and regulate the contract between the employer and the employed, the Association would have done a notable good to the whole community.”[156] But not everyone agreed. In editorials published before the Annual Meeting, the Albany Law Journal decried the committee’s chosen subject as “not such a one as a purely legal association would care about having discussed,”[157] and hoped that “subjects more completely legal in their nature than the present one, may be designated hereafter.”[158]

Before presenting the prize – a generous $250 – Chief Judge Church made a brief address. A man of “commanding stature, robust physique, and distinguished presence,”[159] he expressed gratification with the Association’s formation and confidence it would meet with public favor. He said the Association would “tend to produce cordiality of feeling among the members, and between the profession and the bench,” and “repress evil practices and elevate the standard of education and conduct.” Then, channeling the criticism of the Committee on Prizes, Church offered the following “caution” in the Association’s management:

“That it confine itself strictly to its legitimate object of reforming abuses, and elevating the professional standard, and refrain from interfering with matters foreign to them. If it will do this, it will be eminently successful; if not, dissension will be engendered, and it will likely fail.”

The members broke out in applause.[160]

Shepard made a proposal that the Association’s corporate seal bear an image of Chancellor James Kent’s head and the motto “Deus Optimus Maximus Legislator Solus,” Latin for “God, Utmost and Greatest, the Sole Legislator.”[161] The proposal was referred to the Executive Committee, which, several months later, opted instead for a seal with two concentric circles, inserting between the inner and outer circles the words “New York State Bar Association” at the top and “1876” at the bottom. In the center was a scroll bearing the Latin word “Justicia,” meaning Justice.[162] The seal doubled as the Association’s logo, which remained in use through 1969.

The meeting adjourned and the members went to dinner at Albany’s Delevan House. Delighted over the Annual Meeting’s success,[163] prominent lawyers, politicians and Supreme Court justices from around the state feasted on a sumptuous meal. The head waiter remarked to a reporter: “It is not often so large a company of prominent judges and lawyers gather at dinner as are here now.”[164]

The host of worthies that established the Association built better than they knew. In just two years, the Association was poised to move from strength to strength. As the Executive Committee reported at the Annual Meeting: “The machinery is in thorough working order; and if the leading members of the profession in the state will direct its energies, much may be accomplished.”[165]

In the years that followed, Porter’s vision was realized. The Association has endured and had a collective and permanent influence. The delegates who assembled in the old state Capitol in 1876 would be amazed by the Association’s current technological capacity and programming; impressed by its efforts to do the public good; and inspired by the spirit of collegiality among the members. Indeed, for 145 years the Association has protected the citizenry’s rights and shaped the development of the law, by serving as a resource for all three branches of government.

The founders justly hold a place of honor in the Association’s long and rich history. Their example is one that the present generation may refer to with pride and gratitude.

Henry M. Greenberg is a shareholder at Greenberg Traurig. He served as president of the New York State Bar Association from 2019 to 2020.

[1] See Richard White, The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865–1896, 288, 303–05, 680–81 (2017) (hereinafter Republic for Which It Stands); William H. Rehnquist, Centennial Crisis: The Disputed Election of 1876, 7–8 (2004) (hereinafter Disputed Election of 1876); David McCullough, The Great Bridge: The Epic Story of the Building of the Brooklyn Bridge (1972).

[2] See Lawrence M. Friedman, A History of American Law, 495 (3d ed. 2005) (hereinafter History of American Law) (“For most of the nineteenth century, no organization even pretended to speak for the bar as a whole, or any substantial part, or to govern the conduct of lawyers. Lawyers formed associations, mainly social, from time to time; but there was no general group until the last third of the century.”); Phillip J. Wickser, Bar Associations, 15 Cornell L. Q. 390 (1930) (discussing history of bar associations from colonial era to early 20th century).

[3] State bar associations were formed in New Hampshire in 1873, Iowa in 1874 and Connecticut in 1875, but each, in their original incarnations, were short-lived or ineffective. See History of American Law, supra note 2, at 496 (noting that the Iowa association had a “brief span of life”); A.J. Small, Bibliographical and Historical Check List of Proceedings of Bar and Allied Associations 7 (1923) (“An early New Hampshire State association was organized August 14, 1873, the last meeting begin held August 16, 1878, it apparently having had an existence of about five years”: “On May 27, 1874, the lawyers of Iowa formed an association and held annual meetings until 1881. A new association was organized in 1895”) and 25 (Connecticut Bar Association did not hold regular meetings until 1910).

[4] Kermit L. Hall, David S. Clark & James W. Ely, The Oxford Companion to American Law 244 (2002).

[5] 11 Alb. L.J. 405 (June 26, 1875).

[6] For a history of the City Bar’s founding, see George Martin, Causes and Conflicts: The Centennial History of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, 1870–1970 (1997) (hereinafter Causes and Conflicts); Albert P. Blaustein, New York Bar Associations Prior to 1870, 12 Amer. J. of Legal Hist. 50, 50–51 (1968).

[7] 12 Alb. L.J. 353 (Dec. 4, 1875) (quoting first address of City Bar’s executive committee).

[8] 13 Alb. L.J. 171 (March 11, 1876). See also Isaac Grant Thompson, in 3 New York State Bar Association, Reports 29–32 (1880).

[9] 11 Alb. L.J. at 405. In a similar vein, the Journal wrote in December 1875: “For the sake of the profession such an organization is every way desirable. But beyond and above this, for the sake of the state – for the sake of jurisprudence – the administration of justice – such an association is necessary.” The Journal observed that the bar in England was an “important Factor of the government,” whereas in New York lawyers were “divided and dispersed” and not a “collective force.” 12 Alb. L.J. at 353.

[10] Shepard was a City Bar member and chairman of its Special Committee on the Municipal Code. 11 Alb. L.J. 227 (April 3, 1875).

[11] See Mrs. Elliott Fitch Shepard, in Prominent Families of New York: Being an Account in Biographical Form of Individuals and Families Distinguished as Representatives of the Social, Professional and Civic Life of New York City 504 (Lyman Horace Weeks, ed., 1898) (hereinafter Prominent Families).

[12] See Elliott F. Shepard Dead – Expires At His Home After Taking Ether. Had Given No Indication Of Serious Illness – But Evidently Had The Possibility Of Death In Mind – His Family At His Bedside – A Peculiarly Eccentric Character – Politician, Editor, And Religious Enthusiast – Often Amusing, But Always In Earnest, N.Y. Times, 1893, at p. 1, col. 7; Shepard, Elliott F., in 1 The National Cyclopedia of American Biography Being the History of the United States 159–60 (1893) (hereinafter Shepard, Elliott Fitch); Shepard, Elliott Fitch, in 39 New American Supplement to the New Werner Twentieth Century Edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica 74 (1905); Elliott F. Shepard, in Proceedings of the New York State Bar Association, Seventeenth Annual Meeting 211–13 (1894) (hereinafter Elliott F. Shepard). Shepard’s fortune was attributable, in part, to his wife, Margaret, the granddaughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt, the famous shipping and railroad tycoon. See generally, T.J. Stiles, The First Tycoon: The Epic Life of Cornelius Vanderbilt (2009).

[13] See Jack Henke, Lawyers and the Law in New York: A Short History and Guide 26 (1979) (hereinafter Lawyers and the Law) (“Elliott F. Shepard, a noted lawyer, set in motion the committees, subcommittees, boards and appointees that, after laboring for a full year, brought together ninety-one delegates in the Old Capitol building in Albany to set up the state bar association.”). Shepard was the Association’s fifth president, serving in 1884.

[14] 1 New York State Bar Association, Reports 2 (1878) (hereinafter 1 NYSBA Reports). This volume – the Association’s first annual report – was published under the supervision of the Executive Committee. See New York State Bar Association, Minutes of Executive Committee 1876–1881, at 28, 34 (hereinafter Minutes of Exec. Committee); 2 New York State Bar Association, Reports 53 (1879) (hereinafter 2 NYSBA Reports); The New York State Bar Association, 17 Alb. L.J. 435 (June 1, 1878). The Association published annual reports through 1968, making them available to law libraries throughout the nation.

[15] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 2 (“The president [of the City Bar] appointed the committee as follows: Elliott F. Shepard, Albert Matthews, Clifford A. Hands, Hamilton Odell, R. W. De Forrrest. After a few months’ service, Mr. De Forest resigned, and Mr. Cadwallader E. Ogden was appointed in his place on the committee.”); Francis Bergan, History of the New York State Bar Association – A Century of Achievement, 48 N.Y. St. B.J. 514, 516 (1976) (hereinafter A Century of Achievement) (quoting minutes of City Bar’s October 12, 1885 meeting).

[16] The Shepard Committee’s work is detailed in its report issued in December 1875. The report was printed in full in the New York Daily Register, Vol. IX, No. 90, at 737–38 (April 17, 1876) (hereinafter Committee Report).

[17] Committee Report, supra note 16, at 737; 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 2.

[18] Id.

[19] Committee Report, supra note 16, at 737; see also 12 Alb. L.J. 385 (Dec. 18, 1875) (reporting on issuance of Shepard Committee report).

[20] Committee Report, supra note 16, at 738.

[21] Id. at 737.

[22] Id. at 738.

[23] In the 1870s, an organizing convention was a well-known instrument of establishment and part of New York’s tradition of holding constitutional conventions to develop fundamental law. For example, the Constitutional Convention of 1867 reorganized the state’s judicial system, recasting the Court of Appeals into its modern form. See Francis Bergan, The History of the New York Court of Appeals, 1847–1932, 90–91 (1985).

[24] New York is currently divided into 13 Judicial Districts. N.Y. Jud. Law § 140.

[25] Committee Report, supra note 16, at 737.

[26] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 2; Committee Report, supra note 16, at 737; The Bar Association; Shall The Courts Be Reformed? Proposed Reorganization of The Courts—Report Of The Committee Appointed To Consider The Matter—The State Bar Association Proposition, N.Y. Times, Dec. 15, 1875, at p. 7, col. 1 (hereinafter The Bar Association).

[27] See Causes and Conflicts, supra note 6, at 23–27 (describing character and career of William M. Evarts).

[28] The Bar Association, supra note 26, at p. 7, col. 1.

[29] See Committee Report, supra note 16, at 737 (noting City Bar adopted report on April 11, 1875); 13 Alb. L.J. 279, 280 (April 22, 1876) (reporting on City Bar’s adoption of report); Bergan, A Century of Achievement, supra note 15, at 518 (quoting minutes of April 11, 1876 City Bar meeting).

[30] See, e.g., A State Bar Association, N.Y. Times, March 3, 1876, at p. 4, col. 3 (hereinafter A State Bar Association) (reporting that establishment of state bar was supported by “a number of lawyers of the highest standing in the central portion of the state”).

[31] The State Bar Association, N.Y. Times, Nov. 3, 1876, at p. 2, col. 3 (hereinafter The State Bar Association).

[32] The State Bar Association: Convention for Its Formation to Meet at Albany on Tuesday Next—Some of the Delegates Who Will be Present, N.Y. Times, Nov. 20, 1876, at p. 8, col. 4. See also L. B. Proctor, Secretary’s Report, in Proceedings of the New York State Bar Association, Twentieth Annual Meeting 70 (1897) (hereinafter Twentieth Annual Meeting) (“The Association went into operation under the approval of the judiciary, a large representation of the bar of the State, State officers and members of the Legislature.”).

[33] A State Bar Association, supra note 30, at p. 4, col. 4.

[34] See The State Bar Association, N.Y. Times, supra note 31, at p. 2, col. 3 (reporting that Shepard Committee sent notices to delegates and alternates regarding the date, time and location of the Convention); Bergan, A Century of Achievement, supra note 15, at 515 (“It seems probable that there had been preliminary work done in the City Bar.”); Causes and Conflicts, supra note 6, at 132 (“Sheppard and his colleagues planned a convention to be held at Albany); Lawyers and the Law, supra note 13, at 26.

[35] 13 Alb. L.J. 406 (June 3, 1876).

[36] New York Herald, June 30, 1876, at 8; A State Bar Association, N.Y. Times, June 29, 1876, at p. 10, col. 4; see also Causes and Conflicts, supra note 6, at 132 (“The first district, New York County, was represented by twenty members of the [City Bar], led by Shepard.”).

[37]A State Bar Association, N.Y. Times, July 18, 1876, at p. 8, col 6.

[38] Albany Evening Journal, June 26, 1876.

[39] The State Bar Association, N.Y. Times, supra note 31, at p. 2, col. 3; Douglas G. Blucher and W. Richard Wheeler, A Neat and Plain and Modern Style: Philip Hooker and His Contemporaries, 1765–1836, 96–100 (1993); Deborah S. Gardner & Christine G. McKay, Of Practical Benefit: New York State Bar Association, 1876–2001 10 (2003) (hereinafter Of Practical Benefit).

[40] See Edwin F. Russell, Our 100th Birthday (1876-1976), 48 N.Y. St. B.J. 512, 512–13 (Nov. 1976) (hereinafter Our 100th Birthday) (“excitement [over the presidential election] was in the air, particularly in New York State, during the time when our State Bar Association was born”).

[41] Disputed Election of 1876, supra note 1; Bret Baier, To Rescue the Republic: Ulysses S. Grant, The Fragile Union, and the Crisis of 1876, 241–96 (2022). Hayes was sworn-in as U.S. President on March 3, 1877. Id.

[42] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 4–10.

[43] State Bar Association. A Permanent Organization. Proceedings Of Yesterday’s Convention at Albany—The More Prominent Gentlemen Present—The Appointment Of Committees, N.Y. Times, Nov. 22, 1876, at p. 5, col. 3 (hereinafter A Permanent Organization).

[44] Of Practical Benefit, supra note 39, at 9–10; Martin W. Cooke, View of the New York State Bar Association as Seen from the Standpoint of Its Twentieth Anniversary, in Twentieth Annual Meeting, supra note 32, at 139.

[45] A Permanent Organization, supra note 43; see also All Sorts, Albany Morning Express, Nov. 22, 1876, at p. 1, col. 3 (describing Convention delegates as a “company of very learned and grave men”).

[46] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 11; A Permanent Organization, supra note 43.

[47] 26 Alb. L.J. 261, 261 (Sept. 30, 1882). For a history of the Onondaga County Bar Association, see https://www.onbar.org/about-us/history (last visited March 10, 2022).

[48] For Chief Judge, Waterloo Observer, Sept. 27, 1883 (reporting on Ruger’s nomination by the Democratic party to run for Chief Judge and election earlier that month to be Association President); see also Suzanne Aiardo, William Crawford Ruger, in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, 226–31 (Albert M. Rosenblatt ed., Fordham Univ. Press 2007) (hereinafter Judges). The general election of 1882 resulted in high office for another Association leader, Grover Cleveland, the vice president for the 8th Judicial District, who was elected governor of New York, on his way to becoming U.S. president a few years later. See 7 New York State Bar Association Reports 100 (1884) (“At the last election, the people took up its [Association’s] President, the Hon. William C. Ruger, and made him the Chief Judge of the State; and they took up its Vice-President for the Eight Judicial District, the Hon. Grover Cleveland, and made him Governor of the State.”) (quoting Elliott F. Shepard).

[49] Wm. C. Ruger, Ontario Messenger, Sept. 28, 1882.

[50] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 11; A Permanent Organization, supra note 43.

[51] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 17; see also A Permanent Organization, supra note 43 (“The proceedings of the convention opened with a suggestion that a committee be appointed to offer a proposition for the consideration of those present; but it was set aside, and a resolution adopted to the effect that in the opinion of the gentlemen present that it was advisable to organize a ‘State Bar Association.’”). The motion to form the Association was made by Judge John J. Armstrong of Queens. 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 17.

[52] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 11–17, 23.

[53] Gerald Gunther, Learned Hand: The Man and the Judge 15–16, 40, 56, 61–64, 69 (1994) (hereinafter Learned Hand). Clifford A. Hand was Learned Hand’s uncle. Id.

[54] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 17.

[55] A Permanent Organization, supra note 43.

[56] Id. (“Mr. Ballard, of Cortland, thought the idea of forming a Bar Association, was one of the noblest projects possible, and he warmly advocated the proposition of Judge Hand, whose motion was agreed to.”); 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 17–18.

[57] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 17–18; A Permanent Organization, supra note 43.

[58] A Permanent Organization, supra note 43.

[59] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 18; Death of Judge Suffern, Peekskill Democrat, March 19, 1881. The draft Constitution was clearly prepared in advance of the Convention, presumably by the Shepard Committee.

[60] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 19–20.

[61] Id. at 27 (Ass’n Const., art. III).

[62] Id. at 28 (Ass’n Const., art III).

[63] Id. (Ass’n Const., art. IV); see also id. at 33 (Ass’n Const., art. XXI).

[64] Id. (Ass’n Const., art. IV).

[65] Id. at 28–29 (Ass’n Const., art. VII, VIII, IX, X, XI and XII). The Committee on Legal Biography “was an important instrument in the ‘cherishing’ of the spirit of brotherhood. Its task was to produce biographical sketches of deceased members of the bar. By celebrating “the lives and characters” of distinguished lawyers, the Association hoped to inspire its members, and all the state’s lawyers, to lead worthy professional lives.” Of Practical Benefit, supra note 39, at 11.

[66] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 32 (Article XVIII). The Association subsequently changed the date of the Annual Meeting to January. See Russell, Our 100th Birthday, supra note 40, at 513 (“In 1884 the date was changed again to the Third Tuesday in January. Finally, the date of the Annual Meeting was the Association was set, as it is now, to the last Friday in January.”).

[67] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 33 (Article XIX).

[68] Russell, Our 100th Birthday, supra note 40, at 513.

[69] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 20.

[70] 45 Alb. L.J. 329 (April 16, 1892).

[71] Porter served as an associate judge of the Court of Appeals from 1865 to 1867. See Albert M. Rosenblatt, John Kilham Porter, in Judges, supra note 48, at 994–98; Grosvenor P. Lowrey, John K. Porter, 4 The Green Bag 45 (Aug. 1892) and John K. Porter, 4 The Green Bag 438 (Sept. 1892).

[72] See Charles E. Rosenberg, The Trial of the Assassin Guiteau 82–83 (1968).

[73] Three Great Advocates, 12 Alb. L.J. 4 (July 3, 1875); see also N.Y. Times, April 12, 1892, at p. 4, col. 2 (eulogy for Porter stating that his death “removes from the bar of New-York almost the last of a famous and remarkable school of lawyers”).

[74] Peckham served as an associate judge of the Court of Appeals from 1887 to 1895, and an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1895 to 1909. See Megan W. Bennett, Rufus W. Peckham Jr., in Judges, supra note 48, at 232–38. Peckham’s father, Rufus W. Peckham, Sr., was an associate judge of the court from 1870 to 1873. See Megan W. Bennett, Rufus W. Peckham Sr., in Judges, supra note 48, at 154–59.

[75] See Obituary – Abraham Van Dyck Dewitt, Albany Argus, March 24, 1912, at p. 7, col. 4; Abraham Van Dyck De Witt, in New York State Men: Biographic Studies and Character Portraits 89–90 (Frederick S. Hill, ed., 1906).

[76] See Edward Mitchell, in Prominent Families, supra note 11, at 407.

[77] See Edward Mitchell in The Association of the Bar of the City of New York Yearbook, 1910, 140–43 (1910); Edward Mitchell Dead –Was a Well Known Lawyer –Graduate and Trustee of Columbia, N.Y. Evening Post, Feb. 15, 1909, at p. 10, col. 5.

[78] Samuel Hand served as an associate judge of the Court of Appeals in 1878. See Joshua Jacobson, Samuel Hand, Judges, supra note 48, at 192–97; Learned Hand, supra note 53, at 3–7. Hand was the Association’s second president, serving from 1879 to 1880. His son, Billings Learned Hand, was a judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit from 1924 to 1951, often considered the greatest American judge to never sit on the U.S. Supreme Court. See Learned Hand, supra note 53.

[79] See supra notes 46 to 49 and accompanying text.

[80] See An Old Militia Leader. –Death Of Major-Gen. Sandford. His Varied Experience in the Citizen-Soldiery –A Veteran of The National Guard –The Story of His Military Career, N.Y. Times, July 26, 1878, at p. 5, col. 5.

[81] See Sudden Death at Rochester – Hon. James L. Angle Passed Away Yesterday, Owego Daily Record, May 5, 1881, at p. 1, col. 5.

[82] See Judge Armstrong Dead, Queens Co. Sentinel, Oct. 21, 1886.

[83] See Horatio Ballard, N.Y. Herald, Oct. 9, 1879, at p. 12, col. 2.

[84] Judges, supra note 48, at 1005.

[85] See Judge Platt Potter, Albany Morning Express, Aug. 13, 2021, at pg. 5, col. 5; The Hon. Platt Potter, Albany Argus, Aug. 12, 1891, at p. 8, col. 4.

[86] Lawyers Spoke About Mr. Peck—In His Death the Genessee County Bar Lost One of Its Best Members, Batavia Daily News, May 18, 1910, at p. 8, col. 2.

[87] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 20–23.

[88] See Obituary – Judge Peter S. Danforth, Albany Argus, Jul 19, 1892, at p. 7, col. 4;

[89] See John Forman Seymour, Utica Weekly Herald, Feb. 25, 1890, p. 4, cols. 2–3; John F. Seymour –Death of a Prominent and Honored Citizen of Utica, Rome Daily Sentinel, Feb. 24, 1890. Seymour’s brother, Horatio, served as governor of New York from 1853 to 1854 and from 1863 to 1864. He was the Democratic Party nominee for president in the 1868 presidential election, won by Ulysses S. Grant.

[90] See Death of Hon. Matthew Hale –One of Albany’s Foremost Lawyers Passes to the Great Beyond, Albany Argus, March 26, 1890, at p. 11, col. 4. Hale was the Association’s ninth president, serving in 1890.

[91] See Government Lawyers, 3 Current Comment and Legal Miscellany 17–18 (Jan 15, 1891) (bio of Abraham X. Parker).

[92] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 23; A Permanent Organization, supra note 43.

[93] See Causes and Conflicts, supra note 6, at 132 * (“Porter had a theatrical style in court and was involved in a number of the famous causes of his day.”); 12 Alb. L.J. at 4 (“If we were called upon to point out [Porter’s] . . . most prominent and potent characteristic, we should say it is his dramatic power”).

[94] The State Bar Association, Albany Morning Express, Nov. 22, 1876.

[95] A Permanent Organization, supra note 43.

[96] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 23.

[97] Id. at 24.

[98] Id.; State Bar Association – Permanent Organization, and Institution of a Prize, Albany Evening Times, Nov. 22, 1876 (setting forth written proposal for the Post-Graduate Prize).

[99] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 24; A PERMANENT ORGANIZATION, supra note 43.

[100] Bergan, A Century of Achievement, supra note 15, at 515.

[101] Minutes of Exec. Committee, supra note 14, at 1–5 (minutes of Nov. 22, 1876 Executive Committee meeting describing adoption of Association’s Bylaws and appointment of committee to make recommendation as to need for further revisions); N.Y. Times, Nov. 23, 1876, at p. 1, col. 6 (reporting on Nov. 22, 1876 meeting); N.Y. Evening Post, Nov. 23, 1876, at p. 1, col. 5 (same); 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 45–48 (text of Association’s Bylaws).

[102] The subcommittee consisted of John K. Porter, Elliott F. Shepard, Clifford A. Hand, Marcus T. Hun and Esek Cowen. Minutes of Exec. Committee, supra note 14, at 2; 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 51.

[103] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 65–66 (report of the Executive Committee read at Annual Meeting on Nov. 20, 1877); see, e.g., Minutes of Exec. Committee, supra note 14, at 13 (minutes describing Executive Committee on May 30, 1877 vote by correspondence on a resolution).

[104] The Executive Committee met in person on January 13 in Albany; July 18 in Saratoga Springs; October 16 in New York City; and November 19 and 20 in Albany. See Minutes of Exec. Committee, supra note 14, at 1–23 (minutes of Executive Committee meetings in 1876); 15 Alb. L.J. 37, 51 (Jan. 20, 1877) (reporting on Jan. 13, 1877 meeting); 16 Alb. L.J. 109, 121–22 (Aug. 18, 1877) (reporting on Nov. 19, 1877 meeting); 16 Alb. L.J. 269, 288 (Oct. 20, 1877) (reporting on Oct. 16, 1877 meeting); 17 Alb. L.J. 109, 121-22 (Aug. 18, 1877) (reporting on July 13, 1877 meeting); Bergan, A Century of Achievement, supra note 15, at 515-16 (summarizing Jan. 13, May 30, and July 18, 1877 meetings).

[105] See 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 65 (Executive Committee originated system for the transaction of its own business, which was to a great degree conducted by correspondence); see also 15 Alb. L.J. 37, 51 (Jan. 20, 1877) (reporting on Jan. 13, 1877 meeting when Executive Committee adopted By-law authorizing district committees to do business by correspondence).

[106] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 45–48 (text of Executive Committee’s Rules and Regulations); Minutes of Exec. Committee, supra note 14, at 6–8 (minutes of Jan. 13, 1877 meeting at which Executive Committee adopted its Rules and Regulations).

[107] See, e.g., Minutes of Exec. Committee, supra note 14, at 9, 10 (minutes of Jan. 13, 1877 meeting at which Executive Committee amended the Association’s bylaws).

[108] Minutes of Exec. Committee, supra note 14, at 6–8 (minutes of Jan. 13, 1877 Executive Committee meeting); 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 65; 15 Alb. L.J. at 51.

[109] Minutes of Exec. Committee, supra note 14, at 10 (minutes of Jan. 13, 1877 Executive Committee meeting); Bergan, A Century of Achievement, supra note 15, at 516. See Hamilton Fish in Biographical Dictionary of the American Congress 1774–1996 1030 (Joel D. Treese, ed., 1997); Chauncey M. Depew Dies of Pneumonia in His 94th Year, N.Y. Times, April 5, 1928, at p. 1, col. 7.

[110] 1877 N.Y. Laws Ch. 210, reprinted in Vol I. NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 51–53; see also 16 Alb. L.J. 1, 20 (July 7, 1877) (reporting on passage of Act); 15 Alb. L.J. 133, 134 (Feb. 24, 1877) (reporting on introduction in Legislature of bill to incorporate Association).

[111] 1877 N.Y. Laws Ch. 210, § 1. The Act also provided, among other things, that the existing Constitution, Bylaws and Executive Committee Rules and Regulations were to be those of the corporation; the officers and committees of the voluntary association became the officers and committees of the corporation; and Executive Committee members became trustees of the corporation. Id. § 3.

[112] See 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 26 (Ass’n Const., art. II) (setting forth objects of the Association, one of which objects was “to cherish a spirit of brotherhood among the members thereof”).

[113] David B. Hill was the Association’s sixth President, serving from 1885 to 1887. Of Practical Benefit, supra note 39, at 15.

[114] 1886 N.Y. Laws Ch. 425; David B. Hill, Governor Hill’s Address as President of the State Bar Association, January 18, 1887, in Proceedings of the New York State Bar Association, Tenth Annual Meeting 38, 40 (1887). This legislation was drafted by Kate Stoneman, the first woman lawyer admitted in New York State. Of Practical Benefit, supra note 39, at 14–15.

[115] In 1901, Kate K. Crennell of Rochester became the first woman member of the Association. See Kate K. Crennel in Proceedings of the New York State Bar Association, Thirty-Second Annual Meeting 429–30 (1909). The Association’s first woman president, Maryann Saccomando Freedman, was elected in 1987. Of Practical Benefit, supra note 39, at 135.

[116] Minutes of Exec. Committee, supra note 14, at 14–18 (minutes of July 18, 1877 Executive Committee meeting); 16 Alb. L.J. at 121–22 (reporting on July 18, 1877 Executive Committee meeting).

[117] Minutes of Exec. Committee, supra note 14, at 14; 16 Alb. L.J. at 121–22.

[118] Specifically, the Executive Committee established a “Committee on Arrangements” and gave it a lengthy to-do list. Minutes of Exec. Committee, supra note 14, at 14–15; 16 Alb. L.J. at 121; see also 16 Alb. L.J. 288 (Oct. 20, 1877) (Porter appointed members of Committee on Arrangements on Oct. 16, 1877).

[119] Minutes of Exec. Committee, supra note 14, at 17–18; 16 Alb. L.J. at 122.

[120] Minutes of Exec. Committee, supra note 14, at 17; 16 Alb. L.J. at 122. In 1877, the Legislature “enacted . . . “a voluminous, intricate Code of Civil Procedure, replacing the short, simple 1848 code.” Robert Allen Carter and James D. Folts, Statutes and Statutory Revision, The Encyclopedia of New York State 1473, 1475 (Peter Eisenstaedt & Laura-Eve Moss, eds., 2005).

[121] See 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 65 (summarizing measures taken by Executive Committee regarding membership over the course of its first year).

[122] See 15 Alb. L.J. 73, 90 (Feb. 3, 1877) (quoting letter from Peckham). The “election” of these members-elect occurred by operation of Article III of the Constitution. 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 27 (Ass’n Const., art. III).

[123] 15 Alb. L.J. at 90.

[124] See Members of the State Bar Association, 15 Alb. L.J. 261, 278 (April 7, 1877) (noting that current list of members was “not a very lengthy one – not nearly so lengthy as it ought to be”).

[125] The Committee on Admissions consisted of four members, one from each judicial district, all of whom practiced in New York for at least ten years. See 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 29 (Ass’n Const., art. VII). The Committee on Admissions first met on January 30, 1877, in Albany, at which meeting it adopted regulations governing the admissions process. Id. at 66 (report of the Committee on Admissions at first Annual Meeting).

[126] Of Practical Benefit, supra note 39, at 11.

[127] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 29 (Ass’n Const., art. VII) and 39–40 (Ass’n bylaws, art. VI); Admission to the State Bar Association, 15 Alb. L.J. 89, 89 (Feb. 3, 1877).

[128] See 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 66 (stating that the initial proposals for members’ admission that came before the Committee on Admissions “were all defective in not complying with the requirements of article 6 of the bylaws, and the secretary was directed to return them for correction”).

[129] 13 Alb. L.J. 423 (June 17, 1876).

[130] 15 Alb. L.J. at 278. Ali Baba is a fictional character in Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, a folk tale from the book One Thousand and One Nights.

[131] See 16 Alb. L.J. 341 (Nov. 17, 1877) (noting “large accession of members during the past two months”); 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 65 (summarizing measures taken by Executive Committee regarding membership over the course of its first year), 66–67 (describing amendment to bylaws); Minutes of Exec. Committee, supra note 14, at 9 (minutes of Jan. 13, 1877 meeting at which Executive Committee reduced Committee on Admission’s quorum requirement from 17 to 5); 15 Alb. L.J. 37, 51 (Jan. 20, 1877) (reporting on reduction to quorum requirement).

[132] See 16 Alb. L.J. 229, 248 (Oct. 6, 1877) (describing contents and “attractive” form of Blue Book and its circulation to “a very large number” of lawyers listed therein); 2 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 65 (referencing Executive Committee’s supervision of Blue Book’s publication); Minutes of Exec. Committee, supra note 14, at 2 (minutes of July 18, 1877 Executive Committee meeting stating that Shepard presented a new edition of Blue Book containing legislative act of incorporation and listing members of the Association); 16 Alb. L.J. 109, 121–22 (Aug. 18, 1877) (same).

[133] Letter from A. V. De Witt to Members-Elect (Sept. 3, 1977). Some lawyers who received the solicitation asked the Albany Law Journal: “[W]hat advantage will membership in this society be to me?” The Journal answered that “every respectable attorney in the State” should join the Association because it was in their personal interest. The Journal explained that the Association would work to make the business of law lucrative and ensure unethical lawyers were punished and the unauthorized practice of law stopped. The Association would also do the public good, because only when lawyers act in unison could they effectively contribute to “securing an honest, a learned and an able bench.” 16 Alb. L.J. 214 (Sept. 29, 1877).

[134] See 16 Alb. L.J. 341 (Nov. 17, 1877) (“the wisdom of the executive committee in practically abrogating the obstructive regulation as to election of members has been thoroughly demonstrated by the large accession of members during the past two months.”).

[135] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 68 (Treasurer Peckham report at first Annual Meeting).

[136] L.B. Proctor, Secretary’s Report, in Twentieth Annual Meeting, supra note 32, at 297.

[137] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 55, 57; The State Bar Association. The Annual Meeting – Opinion Of The New Code –The Prize Essay On The ‘Legal Relations Of Capital And Labor –Officers Elected, N.Y. Times, Nov. 21, 1877, at p. 5, col. 1 (hereinafter The Annual Meeting); State Bar Association, Albany Daily Evening Times, Nov. 20, 2021; 16 Alb. L.J. 372 (Nov. 24, 1877); see also 16 Alb. L.J. 338 (Nov. 10, 1877) (setting forth order of exercises for first Annual Meeting).

[138] The Annual Meeting, supra note 137. Every lawyer in the state was invited to attend the first Annual Meeting. 16 Alb. L.J. 338 (Nov. 10, 1877).

[139] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 57–62.

[140] Twentieth Annual Meeting, supra note 32, at 137 (quoting Martin W. Cooke, the Association’s 7th president); see also The Annual Meeting, supra note 137 (describing Porter’s address as “very interesting and eloquent”); 16 Alb. L.J. 372 (Nov. 24, 1877) (reporting that Porter’s address “was received with great enthusiasm”).

[141] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 57; Syracuse Daily Courier, Nov. 23, 1877 (reporting that Porter’s address was “listened to throughout with marked interest, and repeatedly interrupted with applause”).

[142] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 59.

[143] Id at 59–60; see also id at 58 (“I trust that we shall all work together in a kindred spirit, for the advancement of noble ends, tending to our common prosperity, and to the general benefit of the community.”).

[144] Id. at 58.

[145] Id. at 61.

[146] Id. at 62–63 (referring to Committee on Admissions proposed election of Hayes, new U.S. attorney general, the chief justice of Canada, and others, as honorary members of the Association).

[147] Id. at 68.

[148] Id. at 65–66 (Executive Committee report); 66 (Committee on Legal Biography report); 66–67 (Committee on Admissions report); 68–69 (Committee on Grievances report); 70–71 (Committee on Law Reform report); 72–74 (Committee on Prizes report).

[149] Id. at 92–98. This report was issued by Elbridge T. Gerry, who was the grandson of Elbridge Gerry, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Elbridge T. Gerry was a prominent trial lawyer, philanthropist, and bibliophile whose 30,000-volume library became the foundation of the United States Supreme Court Library. He also founded the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (which still operates today) and was Commodore of the New York Yacht Club. See generally, Shelley L. Dowling, Elbridge Thomas Gerry: An Exceptional Life in Gilded Gotham (2017).

[150] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 86–89.

[151] The State Bar Association. Annual Meeting –President Porter’s Address –The Business Transacted., Albany Evening Journal, Nov. 21, 1877, at p. 1, col. 3 (“The appearance of [Chief Judge Church and Court of Appeals Judge Charles A. Rapallo] was greeted with loud applause.”).

[152] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 82–83, 101–38. The Post-Graduate Prize was open to lawyers admitted to practice for five or more years and awarded annually to the contestant preparing the best essay on a subject pre-selected by the Committee on Prizes. Id. at 72, 76. In August 1877, the committee announced that contestants’ essays should address the following subject: “The Legal Relations of Capital and Labor –the Right of the State to Interfere between Employer and Employed, and what Legislation, if any, should be had on this subject.” The Lawyers Post-Graduate Prize, N.Y. Times, Aug. 28, 1877, at p. 8, col. 4 (announcing rules for Post-Graduate Prize, including subject of essay). The committee received and reviewed 25 essays. 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 72. The winner of the 1877 Post-Graduate Prize, Walter R. Howe, pursued a career in politics and became “one of the best-known young men in New York, and he enjoyed the respect and esteem of all who knew him.” Death Of Walter Howe; Seized With Cramps While Bathing At Newport. His Body Recovered by a Searching Party – Fruitless Efforts of Physicians To Resuscitate Him, N.Y. Times, Aug. 23. 1890, at p. 1, col. 5.

[153] See Republic for Which It Stands, supra note 1, at 345–54 (describing Great Railroad Strike of 1877); see also Jack Beatty, Age of Betrayal: The Triumph of Money in America, 1865-1900 (2007) (a critical, indeed indignant history of the Gilded Age).

[154] Julia S. Falk, Women, Language and Linguistics: Three American Stories from the First Half of the Twentieth Century 35 (1999).

[155] Elliott F. Shepard, Labor and Capitol Are One 25 (10th ed.1886). See also Elliott F. Shepard, supra note 12, at 212–13 (“The Colonel published a pamphlet entitled ‘Labor and Capital Are One,’ which has been translated into various languages, and has had a circulation of more than a quarter of a million copies. In this he declared the modern corporation to be ‘one of the greatest blessings of the nineteenth century, and a distinguishing mark of its civilization.’ He extolled railroads in particular, deprecated strikes, and advocated arbitration in all disputes between employers and employees.”).

[156] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 73 (report of the Committee on Prizes delivered by Elliott F. Shepard at first Annual Meeting).

[157] 16 Alb. L.J. 141 (Sept. 1, 1877).

[158] 16 Alb. L.J. 310–11 (Nov. 3, 1877).

[159] Megan W. Bennett, Sanford Elias Church, in Judges, supra note 48, at 141, 145 n. 11 (quoting Irving Browne, The New York Court of Appeals, Part II, 2 The Green Bag 321, 322 (Aug. 1890)).

[160] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 82–83.

[161] Id. at 85–86. The suggestion by Shepard that the Association’s corporate seal should invoke divine law was undoubtedly the product of his deep religious faith. He was well known “as an ardent and active promoter of the scriptural observance of the Christian Sabbath.” Shepard, Elliott Fitch, supra note 12, at 160. In fact, he purchased a controlling interest in a Fifth Avenue stage line in order to bring a halt to its Sunday service. In a similar vein, he placed a verse of scripture on the front page of the Mail and Express, the newspaper he owned and edited from 1888 until his death in 1893. Id.

[162] Minutes of Exec. Committee, supra note 14, at (minutes of March 28, 1878 meeting in New York City of a special committee of the Executive Committee authorized to adopt the Association’s seal); 16 Alb. L.J. at 122; 2 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 53 (reporting on Executive Committee’s adoption of seal).

[163] The Annual Meeting, supra note 137 (“There is great enthusiasm among the Judges and lawyers over the success of this, the largest meeting of the Bar of the State ever held.”).

[164] A Brilliant Company at Dinner, Kingston Daily Freeman, Nov. 21, 1877, at pg. 1, col. 4 (noting “glittering tables” and a multiple course dinner including soup and “toothsome salad,” served with claret wine).

[165] 1 NYSBA Reports, supra note 14, at 66.