Supreme Shift II: A Conservative Super-Majority Delivers a Decidedly Conservative Term

8.3.2021

Note: This article is a follow-up to “Supreme Shift: What the 6-3 Conservative Majority Means Going Forward,” which appeared in the Jan/Feb 2021 issue.

Did the Supreme Court shift rightward? Did replacing Ruth Bader Ginsburg with Amy Coney Barrett make much of a difference? Were the “liberal” justices routinely relegated to issuing dissents? Did “conservative” justices sometimes join the liberals?

Well, yes and yes and yes and yes.

This past term was chock full of highly charged issues. The court rendered rulings involving church and state,[1] search and seizure,[2] the death penalty,[3] voting rights,[4] LGBTQ rights,[5] immigrant rights,[6] Obamacare,[7] labor unions[8] and other issues having clear ideologically opposing positions.[9] Not surprisingly, the court’s decisional output generated abundant commentary. Also, not surprisingly, the commentary was varied, if not downright contradictory.

The Commentary and the Facts

One commentary reported the Supreme Court to be “fluid and unpredictable,”[10] with the justices “deciding cases narrowly, reach[ing] agreement across the predicted partisan divides.”[11] Another viewed the court as “both ideologically predictable and unpredictable,” but “[t]o be clear . . . more conservative.”[12] Many conservative court watchers complained that “the three newest justices lack intestinal fortitude.”[13] At the same time, “[l]iberal legal activists say their critiques of the Trump appointees were well-justified and the idea that conservatives should feel buyers’ remorse is absurd.”[14] One commentator emphasized that “the Justices repeatedly defied expectations, with conservatives and liberals together forming majorities in high-profile cases.”[15] And yet another insisted that “the muscular conservatism of the Roberts court was in full flower.”[16]

To rephrase an oft-quoted quip of the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York, we may all have our own perspectives, preferences and critiques, but there actually are some facts.[17] To be sure, those facts can be interpreted and extrapolated, highlighted or ignored, celebrated or decried. But being facts, they can’t be denied. So, without adornment, let’s take a look.

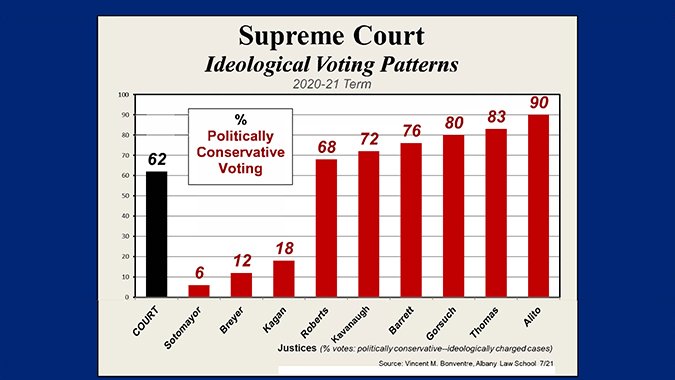

When considering those appeals presenting issues having clearly opposing political or social sides – i.e., “conservative” versus “liberal”[18] – the court’s decisional record was more than 60% conservative.[19] Among the individual justices, the ideological spectrum ranged from Justice Samuel Alito, who voted for the conservative position 90% of the time, to Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who did so on only 6% of the issues.[20]

The ideological divide on the court could hardly have been starker. Contrast the voting records of the three liberal justices who remain since the loss of Ruth Bader Ginsburg – Sotomayor, Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan – with any of the others. The most politically conservative record among the liberals was that of Justice Kagan at 18%. The least politically conservative record among the conservatives on the Court was that of Chief Justice Roberts at 68%.

That ideological chasm is all the more striking when we remember that these justices were considering the very same issues, arising out of the very same facts, in the very same cases. The chasm is especially stark when contrasting the ends of the court’s ideological spectrum. The voting of the court’s three liberals was Sotomayor at 6% conservative, Breyer 12% and Kagan 18%. Contrast that with the voting of Justices Samuel Alito at 90% conservative, Clarence Thomas 83%, and Neil Gorsuch 80%.

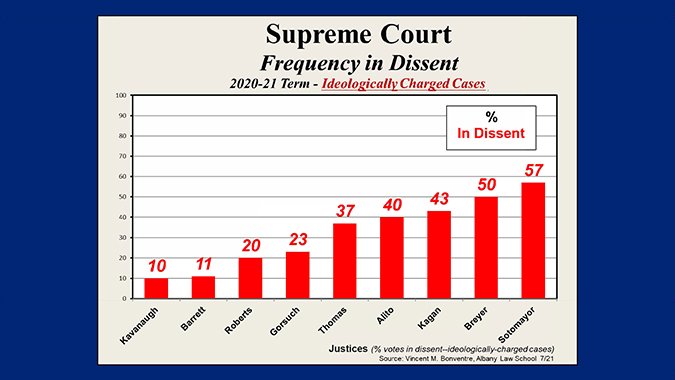

The decisional record of the court as a whole, 62% conservative, is reflected in the respective dissenting rates among the justices.[21] The liberal justices were in dissent far more frequently than the conservatives – from twice as frequently to five times as often, depending on the justices being compared. Consider the least to the most frequently dissenting justices. Among the three liberals, Justice Sotomayor voted against the majority decision on more than half of the ideologically charged issues. Her 57% dissenting rate was followed by Breyer at 50% and Kagan at “only” 43%. The three conservative justices at the other end of the dissenting-rate spectrum were Brett Kavanaugh at 10%, Barrett 11%[22] and Roberts 20%.

The Barrett Difference

With the change in the court’s composition – i.e., the appointment of Amy Coney Barrett to fill the vacancy arising from the passing of Ruth Bader Ginsburg – the ideological balance shifted from a 5–4 conservative majority to 6–3. The significance of that shift, however, cannot be appreciated simply as a change in numerical balance. The difference in how Justice Barrett voted with how Justice Ginsburg would surely have voted makes the point.

Just consider those cases where Justice Barrett voted one way and the court’s remaining three liberals, as a bloc, voted the opposite – and would surely have been joined by Justice Ginsburg. Among Barrett’s votes in criminal cases, opposed by all three liberal justices, were those in Shinn v. Kayer, to reject the ineffective counsel claim of a death inmate;[23] in Jones v. Mississippi, to uphold a sentence of life without parole for a juvenile defendant;[24] and in Edwards v. Vannoy, to deny the retroactive application of the unanimous jury right.[25]

Among Barrett’s votes in civil cases, likewise opposed by the three liberal justices, were those in Roman Catholic Diocese v. Cuomo, to invalidate pandemic restrictions on church services;[26] in Trump v. New York, to dismiss the challenge to Trump’s order to exclude undocumented immigrants from the census;[27] in Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid, to invalidate California’s law expanding union recruitment of agricultural workers on management property;[28] in TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez, to dismiss a class action of private plaintiffs for violations of the Fair Credit Reporting Act;[29] in Johnson v. Guzman Chavez, to deny a hearing to previously removed noncitizens who feared persecution and torture upon deportation;[30] in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, to uphold Arizona’s voting statute criminalizing “ballot-harvesting” and discarding out-of-precinct votes;[31] and in Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta, to invalidate California’s required disclosure of major donors to tax-exempt organizations.[32]

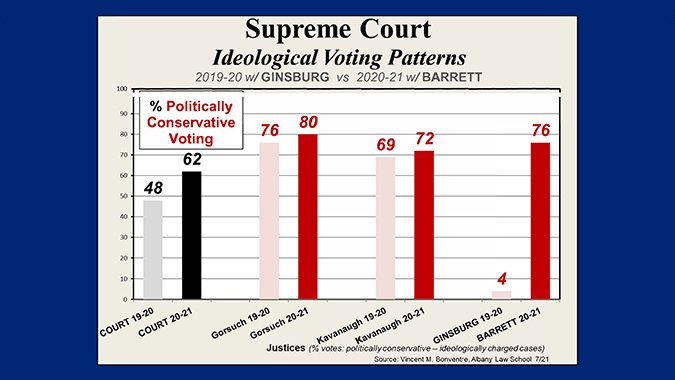

This recitation of Justice Barrett’s votes is in no measure intended to suggest that they are legally mistaken, inequitable, misguided, or in any other sense wrong.[33] It is simply to demonstrate the extent to which her voting this past term contrasts so sharply with what the votes of Justice Ginsburg would have been. Perhaps a visual juxtaposing of their respective voting patterns makes the point most emphatically.[34]

The difference between Justice Barrett’s voting this past 2020–21 term and the voting of Justice Ginsburg in the 2019–20 term could hardly be more vivid. The voting records being compared take account of all the ideologically charged cases in which the court was divided and in which the justices participated in their respective terms.[35] Significantly, the voting of the two other appointees of President Trump – Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh – underwent virtually no change from one term to the next. Gorsuch’s voting was 76% conservative the previous term and 80% this one. Kavanaugh’s was 69% and 72%. The change, however, between Ginsburg’s voting the previous term and Barrett’s this past one was truly dramatic.

Justice Ginsburg’s voting across the pool of ideologically divided cases was 4% conservative; Justice Barrett’s was 76%. Stated otherwise, in her final term on the court, Ginsburg supported the more politically and socially conservative positions in only one of the 27 such cases. Justice Barrett, in her first term on the court, filling the Ginsburg vacancy, supported the more politically and socially conservative positions in 24 of the 27 cases in which she participated. Stating the same thing in terms of liberal positions, Ginsburg supported them in 26 of 27 cases; Barrett did so in only three of the same number.

Considering the drastically contrasting voting of Ginsburg and Barrett, it is no wonder that the court as a whole was more conservative this past term than the term before. An unmistakable shift in the court’s decisional record did coincide with Barrett replacing Ginsburg. Albeit not as dramatic as the Ginsburg-to-Barrett difference in voting, the change in the court’s record was nevertheless considerable. It shifted from being moderately liberal – i.e., less than half conservative, or 48% so in the previous term – to clearly conservative, at 62% this past term. That decisional record was less conservative than the voting of Justices Alito at 90%, Thomas 83% and Gorsuch 80%[36] – and less than Barrett’s own at 76%. But it, nonetheless, represents a shift in a decidedly conservative direction.

Roberts Plus Kavanaugh for Liberal Victories

The Supreme Court’s 62% conservative decisional record this past term does, of course, mean that there were some liberal rulings – 38%, or on a little more than one-third of those ideologically charged issues on which the justices divided. The two justices at the center of the court’s ideological spectrum, Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kavanaugh,[37] were jointly responsible for many of them.

Among the criminal rulings in which the three liberal justices were joined by Roberts and Kavanaugh were Torres v. Madrid, holding that the application of force with the intent to stop, even if the attempt to detain fails, constitutes a 4th Amendment “seizure;”[38] and Lombardo v. City of St. Louis, holding that the “prone restraint” of an inmate, even if he is resisting, may constitute excessive force.[39]

Among the civil cases where Roberts and Kavanaugh supported a liberal majority ruling were Salinas v. United States Railroad Retirement Board, holding that workers who lost their retirement claims at the board were entitled to judicial review;[40] Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. v. Arkansas Teacher Retirement System, placing the burden of proof on the securities fraud defendant, even where the alleged misrepresentation is “generic;”[41] and California v. Texas, dismissing the latest Republican challenge to the Affordable Care Act.[42] Additionally, Chief Justice Roberts voted in dissent with the three liberals in Roman Catholic Diocese v. Cuomo[43] and Tandon v. Newsom,[44] supporting the pandemic restrictions against religious liberty challenges.

One final civil ruling should be noted. In Fulton v. City of Philadelphia, the court unanimously held that a faith-based agency, with religious objections to placing foster children with same-sex couples, was entitled to an available exemption under the local anti-discrimination civil rights law.[45] The justices were divided, however, on the standard to be applied to religious objections.

The majority, in an opinion by the chief justice, based its decision on the religious discrimination it found in the city’s denial of an exemption, which the law itself explicitly permitted. However, three of the justices – Thomas, Alito and Gorsuch – went further and urged reconsideration of the court’s governing 1990 precedent, Employment Division v. Smith.[46]

Under Smith, any “otherwise valid” law that is “generally applicable” defeats religious objections. Strict scrutiny of such laws does not apply. Consequently, for free exercise of religion to prevail, the law in question must be invalid for some other reason, such as discriminating against religion.[47] Overruling Smith – a goal of religious conservatives, apparently including the three justices who urged reconsideration – would fortify free exercise claims by reinstating strict scrutiny. It would then be much easier for religious objectors to succeed against civil rights laws, even if those laws were generally applicable.

But Chief Justice Roberts – writing for himself, the three liberal justices, and Justices Kavanaugh and Barrett –chose the narrower route to requiring a religious exemption in Fulton. Roberts’ majority declined to reconsider Smith and further dilute the effectiveness of civil rights laws. Instead, the religious objectors prevailed in Fulton, under Roberts’ majority opinion, only because the civil rights law at issue did permit exemptions, and denying one to the objectors was deemed to be discriminatory.

This 6-3 Conservative Court

There was little doubt that the appointment of Amy Coney Barrett to replace the deceased Ruth Bader Ginsburg would affect the Supreme Court’s decisional direction. There was no doubt – none realistic anyway – that Barrett’s voting would be very different from what Ginsburg’s had been.

Justice Ginsburg was well-recognized as a liberal icon. Her voting record was socially and politically very liberal, placing her well within the liberal side of the court’s ideological spectrum. In fact, her record was consistently at or near that spectrum’s liberal extreme.[48]

Justice Barrett’s record prior to her appointment, while a federal appellate judge on the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals, was quite socially and politically conservative.[49] Unless she were to experience a dramatic ideological conversion, it could confidently be predicted that her record at the Supreme Court would be similarly quite conservative and, therefore, quite different than the record of the justice she replaced. As we have now seen, Barrett underwent no such conversion. Ginsburg’s record of 4% conservative voting was replaced by Barrett’s 76%.[50]

Together with Justices Alito, Thomas, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Chief Justice Roberts – listed here in descending order of voting-record conservativism – Barrett is part of a formidable conservative super-majority. The impact on the court’s decisional leaning should not be underestimated

It might well seem that this emphasis on “conservative” versus “liberal” justices is overdone. To be sure, in a given case, the liberal justices might be joined by Roberts and Kavanaugh, or by some other combination of their conservative colleagues, to form a majority. But overall? Consider what the 6–3 conservative-liberal imbalance most likely means.

Consider, for example, issues before the Supreme Court that entail crime control on one side versus more protection for the accused on the other; upholding a death sentence on one side versus severely restricting or abolishing its use on the other; abortion restrictions versus the right to choose; religious liberty versus LQBTQ rights or health restrictions; color-blindness versus affirmative action; gun rights versus gun control; voting requirements versus the right to vote; management prerogatives versus worker rights; unhampered business versus health, safety and wage regulations; immigration restrictions versus immigrant rights; property rights and development versus environmental protection; and, in general, “traditional” values versus social and political change. These and other ideologically charged issues can usually be expected to trigger competing “conservative” versus “liberal” positions among the justices.[51]

Again, to be sure, even with a 6–3 conservative majority, the court will likely render some rulings that strengthen the rights of the accused, reverse a particular death sentence, invalidate some harsh treatment of immigrants, uphold the application of some anti-discrimination law, invalidate some voting restrictions, and uphold some gun regulations, as well as other decisions urged by the three liberal justices.

But make no mistake, the Supreme Court is far different today, and its decisional record has been and will very likely continue to be far different, than would be true if the court’s composition were a 6–3 – or even 5–4 – liberal majority. For better or worse, the current court, with the three conservative Trump appointees, is a far different institution, with a far different ideological tilt, and with predictably far different decisional outputs, than would have been true with liberal appointees.

If Justice Ginsburg had been replaced with a more like-minded appointee, and the remaining liberal justices on the court had been joined with appointees who gave them a liberal majority, the court’s decisional record, this past year and in the years to come, would almost certainly be the reverse.

Vincent Martin Bonventre is Justice Robert H. Jackson distinguished professor of law, Albany Law School.

[1]. Roman Catholic Diocese v. Cuomo, 141 S.Ct. 63 (2020) (New York’s pandemic restrictions discriminate against religion).

[2]. Torres v. Madrid, 141 S.Ct. 989 (2021) (physical force with intent to stop constitutes a seizure).

[3]. Shinn v. Kayer, 141 S.Ct. 517 (2020) (denial below of death inmate’s ineffective counsel claim was not clearly erroneous).

[4]. Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, 141 S.Ct. 2321 (2021) (state voting restrictions do not violate the Voting Rights Act).

[5]. Fulton v. City of Philadelphia, 141 S.Ct. 1868 (2021) (religious agency entitled to exemption from state anti-discrimination law).

[6]. Johnson v. Guzman Chavez, 141 S.Ct. 2271 (2021) (illegally reentering alien not entitled to hearing on risk of persecution and torture upon deportation).

[7]. California v. Texas, 141 S.Ct. 2104 (2021) (states challenging Affordable Care Act have no standing).

[8]. Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid, 141 S.Ct. 2063 (2021) (state law providing union’s right to organize on owner’s land constitutes unlawful taking).

[9]. Regarding the terms “liberal” and “conservative” as representing ideologically opposing positions, see the discussion, ‘LIBERAL’ JUSTICES, ‘CONSERVATIVE’ JUSTICES, in my previous article in this journal, Supreme Shift: What the 6-3 Conservative Majority Means Going Forward, 93 NYSBA Journal 9 (Jan./Feb. 2021) (hereafter, “Supreme Shift I”).

[10]. Adam Liptak, A Supreme Court Term Marked by a Conservative Majority in Flux, NY Times, July 2, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/02/us/supreme-court-conservative-voting-rights.html.

[11]. Id. (quoting David Cole, the national legal director for the American Civil Liberties Union).

[12]. David Leonhardt, A Supreme Court, Transformed, NY Times, July 6, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/06/briefing/supreme-court-donald-trump.html.

[13]. Josh Gerstein, Trump’s Supreme Court Shrinks From Controversy, Politico, July 7, 2021, https://www.politico.com/news/2021/07/07/trump-supreme-court-courage-498459.

[14]. Id.

[15]. Jeannie Suk Gersen, The Supreme Court’s Surprising Term, The New Yorker, July 5, 2021, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/07/05/the-supreme-courts-surprising-term.

[16]. Leah Litman and Melissa Murray, Opinion: Don’t Be Fooled: This Is Not a Moderate Supreme Court, Washington Post, July 1, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/07/01/make-no-mistake-this-is-conservative-supreme-court-it-just-sometimes-acts-slowly/.

For a somewhat different view of the Roberts court – or at least of the chief justice as an institutionalist – see, in an earlier issue of this journal, Joseph W. Bellacosa, ‘Guardian of the Institution,’ NYSBA Journal (2019), https://archive.nysba.org/Journal/2019/Dec/%E2%80%98Guardian_of_the_Institution%E2%80%99/.

[17]. In the interest of full disclosure, I am a fairly liberal Democrat who, however, is viewed as somewhat conservative by many other liberals, but a “leftie” by many conservatives. If I were on the court – Lord forbid – I would be aligned most regularly with Justice Elena Kagan and Chief Justice John Roberts.

[18]. As discussed in Supreme Shift I, these are the ideologically charged “hot-button,” issues, the issues where, for example, “conservative” Republican politicians and voters would typically support one position, while “liberal” Democratic politicians and voters would typically support the other. Anyone who follows politics and courts can surely identify a list of such issues. Among the most salient are those dealing with the separation of church and state, gun rights, LGBTQ rights, abortion, affirmative action, immigration, the death penalty, business regulation, and in recent years, just about anything involving President Obama or Trump. 93 NYSBA Journal 9 (Jan./Feb. 2021).

[19]. The court issued a total of 67 decisions in which it resolved the merits, whether substantive or procedural. Source: SCOTUS blog, Stat Pack for the Supreme Court’s 2020-21 term, July 2, 2021, at 4.Among those 67, I identified 30 that presented “conservative” versus “liberal” sides on which the justices were divided.

Notably, an ideological divide sometimes occurs among justices who vote for the same disposition in a case – e.g., a reversal – and yet the majority and concurring opinions embrace different rules of law where one is more “liberal” and the other more “conservative.” For example, in Goldman Sachs Group Inc. v. Arkansas Teacher Retirement System, 141 S.Ct. 1951 (2021), involving a class action for securities fraud, the majority and concurring opinions agreed that the case should be remanded. But the majority placed the burden to disprove the alleged generic misrepresentation on the defendant, while the concurring opinion argued that the plaintiffs should bear the burden of proving it.

[20]. See the graph entitled “Supreme Court, Ideological Voting Patterns, 2020-21 Term.”

The focus on ideological patterns – i.e., “conservative” versus “liberal”—might seem overdone. But see the discussion infra under ”This 6-3 Conservative Court.”

[21]. See the graph entitled “Supreme Court, Frequency in Dissent, 2020-21 Term – Ideologically Charged Cases.”

[22]. Justice Barrett did not participate in several of the early appeals while her nomination was being considered – three of them among the total pool of 30 non-unanimous ideologically charged cases – and, consequently, her total number of cases and corresponding percentages do not align with those of the others on the court.

[23]. See supra note 3. See also Dunn v. Reeves, 141 S.Ct. 2405 (2021) (Barrett voting with majority that the state court did not clearly violate federal ineffective counsel law).

[24]. 141 S.Ct. 1307 (2021) (life without parole may be imposed without finding that the juvenile is permanently incorrigible).

[25]. 141 S.Ct. 1547 (2021) (the rule announced in Ramos v. Louisiana (2020) does not apply retroactively on federal collateral review).

[26]. See supra note 1. See also Tandon v. Newsom, 141 S.Ct. 1294 (2021) (California’s pandemic restrictions discriminate against religious gatherings).

[27]. 141 S.Ct. 530 (2020) (the predicted injuries from the presidential policy is insufficient to satisfy standing).

[28]. See supra note 8.

[29]. 141 S.Ct. 2190 (2021) (plaintiffs failed to show concrete injury to satisfy standing).

[30]. See supra note 6.

[31]. See supra note 4.

[32]. 141 S.Ct. 2373 (2021) (compelled disclosure of the identities of major donors violates the First Amendment freedom of association).

[33]. Again, I may have my own preferences as much as anyone else (see supra note 17), but that is not the point here.

[34]. See the graph entitled “Supreme Court, Ideological Voting Patterns, 2019-20 w/ GINSBURG vs 2020-21 w/ Barrett.”

[35]. The pool for the past term includes 30 such non-unanimous ideologically charged cases. (See supra note 19.) Justice Barrett participated in 27 of them. (See supra note 20.) The previous year, the analogous pool totaled 27 cases. (See Supreme Shift I, supra note 9, at n. 23 and accompanying text.)

[36]. See the graph above entitled “Supreme Court, Ideological Voting Patterns, 2020-21 Term.”

[37]. Id. Roberts’s 68% conservative voting record and Kavanaugh’s 72% were significantly less conservative, for example, than the records of Alito at 90% and Thomas at 83% – the most conservative records among the Court’s 6 to 3 conservative majority.

[38]. 141 S.Ct. 989 (2021), supra note 2. Justice Barrett also joined in the majority.

[39]. 141 S.Ct. 2239 (2021).

[40]. 141 S.Ct. 691 (2021).

[41]. 141 S.Ct. 1951 (2021), supra note 19. Justice Barrett joined the majority and authored the court’s opinion.

[42]. 141 S.Ct. 2104 (2021), supra note 7. Justices Thomas and Barrett also joined the majority’s ruling that the challengers lacked standing.

[43]. 141 S.Ct. 63 (2020), supra note 1.

[44]. 141 S.Ct. 1294 (2021), supra note 26.

[45]. 141 S.Ct. 1868 (2021), supra note 5.

[46]. 494 U.S. 872 (1990) (free exercise of religion claims do not trigger strict scrutiny where the law in question is “otherwise valid”—e.g., it is “generally applicable” and, thus, does not discriminate against religion).

[47]. See generally, Vincent Martin Bonventre, Religious Liberty: Fundamental Right or Nuisance, 14 U. St. Thomas L.J. 650 (2018).

[48]. For example, in her final year on the court, the 2019–20 term, Ginsburg’s voting record was 96% liberal – or, as discussed above, only 4% conservative (see supra notes 34–35 and accompanying text) – meaning she supported the more liberal position in 26 of the 27 ideologically charged issues that divided the justices.

The previous year, the 2018–19 term, for the cases I identified at that time as presenting issues with competing ideological positions on which the justices divided, Ginsburg voted for the liberal side 100% of the time, or on every one of 25 ideologically charged issues.

[49]. See Supreme Shift I, supra note 9, at 11–13.

[50]. See supra notes 34-35 and accompanying text; see graph entitled “Supreme Court, Ideological Voting Patterns, 2019-20 w/ GINSBURG vs 2020-21 w/ Barrett.”

[51]. See supra note 18.