Bored Apes and Monkey Selfies: Copyright and PFP NFTs

12.16.2022

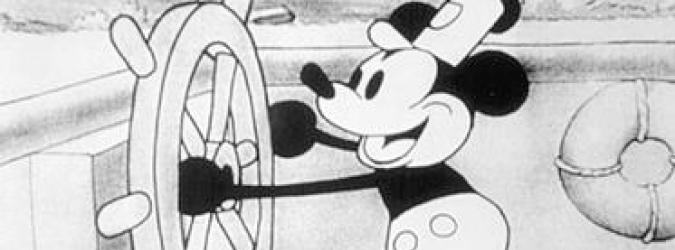

What do the monkey selfie and the “Bored Ape Yacht Club” images pictured above have in common? Both depict grinning primates, of course. But less obviously, both may lack copyright.

You may recall a dispute between Naruto the monkey and a photographer whose camera Naruto borrowed to take a selfie. The photographer argued that he owned copyright of the photo, while Naruto argued, through People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), that Naruto owned it. The Ninth Circuit ended the dispute by affirming the district court’s ruling that monkeys can’t sue humans.

For different but related reasons, “Bored Ape” NFTs may also lack copyright. In what follows, I’ll explore this and other surprises arising from the collision of copyright law and profile picture NFTs, or PFPs.

Since Larva Labs debuted “CryptoPunks” in 2017, PFPs have been the reigning format for NFTs. Aesthetically, the format permits variation within a standard template on a scale that Andy Warhol would have envied. Economically, it lets creators supply a critical mass of semi-fungible intangible assets capable of sustaining an ecosystem of collecting, trading and speculation. So it’s no accident that the most successful NFT projects are PFPs.

Regardless of the merits of PFPs to date, they undoubtedly constitute a new and important artistic medium, with emerging aesthetics, economics and cultures attributable to their form. Aside from making this observation, I won’t try to convince anyone of its truth here. Instead, I’ll suggest a definition for PFPs and discuss their strange copyright implications.

Definition

By PFP, I mean a collection of NFTs:

- With many images.

- Based on a template.

- Depicting anthropomorphic subjects.

- That vary based on a given set of traits (e.g., background, eyes, mouth).

- That are automatically assembled by selecting layers corresponding to trait types from a digital file.

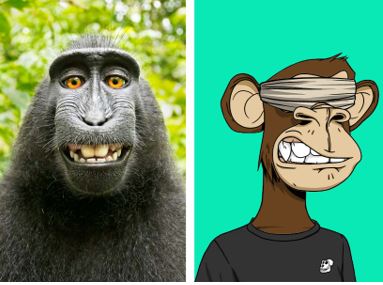

Here’s a stock photo showing several images from the “Bored Ape Yacht Club,” NFT collection, the quintessential PFP:

Copyright in PFPs

PFPs raise many copyright questions. For example, artist and legal scholar Brian Frye has questioned whether “CryptoPunks” merit copyright protection at all.[i] Each “CryptoPunk” is a highly simplified, 24 x 24 pixel, 8-bit image. Here’s a theoretical “CryptoPunk ,”[2] enlarged for easy viewing:

There are several reasons why a “CryptoPunk” may not merit copyright protection:

- It lacks a minimum of creative authorship.

- There are too few ways to express the same idea (the “merger” doctrine).

- It wasn’t created by a human, but assembled by code.

- It wasn’t independently created; i.e., it’s based on an earlier work.

I’ll ignore the last reason because it’s obvious enough – if Larva Labs based a “CryptoPunk” on an earlier work but didn’t add enough original content, then that “CryptoPunk” wouldn’t be copyrightable. But I will discuss the other reasons.

Insufficient Creativity and the Merger Doctrine

I have anecdotal evidence that the U.S. Copyright Office is unlikely to refuse to register simple pixel art because it’s insufficiently creative or falls prey to the merger doctrine. On April 1, 2022, I received a copyright registration on “CryptoSkull 7347”:

Still, we may see this question litigated if copyright owners try to enforce their rights in a “CryptoPunk” or another work of simple pixel art.

Automatically Assembled Works

A more interesting question for PFP copyrightability relates to how they’re generated. As I mentioned in my definition, PFPs are created from a set of traits, each of which may have many possibilities whose permutations allow for many unique works. These permutations are generally created by a computer implementing an automated procedure.

For example, the PFP “The Jims” has the following traits, with the number of possibilities for each noted in parentheses: accessory (7), background (15), body (12), eyes (10), head (13), and mouth (10). These traits allow for 1,638,000 permutations, of which the creators gave us 2,048. Here’s an example, “Jim #524”:

Is “Jim #524” protected by copyright? Certainly, the individual traits may be separately copyrightable if they pass the minimally creative threshold. Here are “Jim #524”’s mouth (underbite) and head (lemur) by themselves:

But is there any copyright to the whole apart from its traits? Only if the procedure for selecting traits suffuses it with human authorship. Because the creators could have generated all 1,638,000 permutations, but chose to generate less than 0.125% of them, human authorship is conceivable, but it might come down to how the selection procedure was written. Even though a small percentage of permutations was created, it isn’t apparent how an automated process would result in human authorship.

The NFT Owner’s Copyright Interest

Creators grant varying rights to NFT owners in the associated works, but the following four approaches are most common:

- Say nothing, leaving NFT owners with at best an implied license.

- Grant an express license, usually to display the works for non-commercial purposes.

- Transfer all rights in the works to the owners.

- Make the works public domain.

The strangest results arise from the third approach, namely, purported transfers of all rights to PFP owners.

Transfer of Copyright by Transfer of NFT

Can one transfer copyright in a work associated with an NFT solely by transferring the NFT? Without more, the answer is no – there must be a statement that transfer of the NFT constitutes transfer of the associated work. So to refine the question, is it possible to transfer copyright in a work associated with an NFT by (1) stating that copyright ownership is mediated by ownership of the NFT and (2) transferring the NFT?

For example, Yuga Labs (creators of the “Bored Apes”) states in its terms, “When you purchase an NFT, you own the underlying Bored Ape, the Art, completely.”3 The creators of “CryptoSkulls” are even clearer in their terms:

“It is our opinion that a blockchain transaction satisfies the legal requirement for copyright transfer. So copyright ownership of each individual image is adjudicated by the Ethereum/Polygon address for which the non-fungible token (NFT) of that image is assigned.”

But do these statements work? To transfer exclusive rights in a copyrighted work, the Copyright Act requires a written statement signed by the copyright owner. The signature may be of the standard ink variety, but digital signatures also work.

Does a Covenant To Transfer Copyright With the NFT Run With the NFT?

Let’s use “Bored Apes” as an example. If I created (or “minted”) an “Ape,” the question would be whether Yuga transferred the copyright to the “Ape” to me with a written signature. Arguably Yuga did so by making a public statement on its website that the NFT buyer “own[s] the underlying Bored Ape, the Art, completely,” but we’ll have to wait for a court to opine on that question to be sure.

Things get even more complicated with subsequent transfers. Let’s assume that Yuga required me to agree to its terms as a condition to minting my “Ape.” Then, arguably, I have agreed that “[o]wnership of the [digital artwork] is mediated entirely by the Smart Contract and the Ethereum network.” So when I “sign” the blockchain transaction with my private key to transfer the NFT, I’m arguably transferring all rights in the associated work.

But after that point, things get more contingent and may depend on how the NFT is transferred. For example, assume I sell the “Ape” on OpenSea, and then it is resold on OpenSea several times. The OpenSea Terms of Service state:

NFTs may be subject to terms directly between buyers and sellers…. For example, when you click to get more details about [an NFT]….,

you may notice a…… link to the creator’s website. Such website may include [t]erms… that you will be required to comply with.

Each buyer of the “Ape” on OpenSea would’ve been directed to consider the BAYC terms via the OpenSea terms and, as a result, is arguably bound by them. So if the blockchain signature constitutes a written signature for Copyright Act purposes, all rights remain with the NFT owner.

But what if the “Ape” were sold on a marketplace lacking such terms or transferred in a private sale? Unless the seller presents the buyer with the BAYC terms, the buyer arguably is not bound by them and, if not, may transfer the NFT without transferring the copyright in the associated work.

Potential Solutions for Keeping Copyright With the PFP Owner

PFP creators who want the copyright to remain with the PFP owner can minimize these problems by associating terms more closely with the NFT. That can be done by including a link to terms (or better, the terms themselves) in the metadata for the NFT, by prominently displaying the terms in comments to the code that generates the NFT (the smart contract) or both. The most careful creators even include the terms in the NFT itself.4

Problems for PFP Creators Who Transfer Copyright to PFP Buyers

When a PFP creator purports to transfer copyright to buyers, what happens to the copyrights that exist in the associated works as each PFP is minted? Consider “Ape #ABCD”5 and “Ape #4485”:

So when “Ape #2” is minted (by “Minter #2”), Minter #1 has a claim against Yuga for infringing Minter #1’s exclusive rights to reproduce, distribute, prepare derivative works based upon and publicly display either (1) the work as a whole, (2) its traits or (3) both. Minter #2 may also have claims against Yuga for breaching express and implied warranties of non-infringement. And at best, Minter #2 would own the thinnest of copyrights in the image without the earring, which would be subject to Minter #1’s superior and all but coextensive rights.

Assuming this analysis holds, some strange results follow. First, Yuga has no rights in the “Apes” at all, having given them away piecemeal to its minters. Second, as each “Ape” was minted, each subsequent “Ape” received exponentially narrower rights.

If correct, Yuga has no right to reproduce, prepare derivative works based upon, distribute or display any “Ape” or any of their copyrightable traits. Moreover, any “Ape” owner who owns a right that is not subject to another “Ape” owner’s rights may have a claim for copyright infringement against Yuga.

Commercial ventures featuring “Apes” may also be at risk of copyright infringement suits. Consider KING- SHIP, the musical group consisting of three “Apes” and one “Mutant Ape,” signed by Universal Music Group. In particular, consider “Ape #7796,” which has an aquamarine background, white fur, striped T-shirt, and laser eyes. “Ape #118” and “Ape #3015” predate “Ape #7796,” as do 7,794 other “Apes.” “Ape #118” is identical to “Ape #7796” except for its “tan fur” and “bored kazoo” mouth, while “Ape #3015” is identical to “Ape #7796” except for its “short mohawk” and “wide eye[s].”

Arguably, the owner of “Ape #7796” has no copyright in the “Art” or any of its traits, all of which appear in earlier-minted “Apes.” Or, assuming copyright exists in the “Art,” at best, “Ape #7796”’s owner has a copyright in a compilation of traits that is graphene-thin, subject to many earlier works and all but unlicensable.

On the other hand, the first few “Apes” minted have a relatively broad (though exponentially narrowing) scope of copyright protection, to which all subsequent “Apes” are subject, making them far more valuable from a potential licensing perspective.6

Potential Objections

I’m sufficiently confident with my analysis that I have no fear in creating and tweeting my own “Ape” that includes the rarest possible trait in each category:

If you don’t like my analysis, what are the alternatives? You might argue that Yuga never intended to transfer copyright to “Ape” minters.7 But even if that were true with respect to the “Apes,” it doesn’t apply to other PFPs that clearly intend to transfer all copyright to buyers (e.g., “CryptoSkulls”).

You might also argue that PFPs haven’t met the written signature requirement for copyright transfer, giving buyers only non-exclusive rights in the associated works and leaving the PFP creator with all copyright.

Another objection would be that all the players here – PFP creators and buyers alike – understand that thousands of similar, overlapping works are going to be minted and that, as a result, PFP buyers have no claim against PFP creators for copyright infringement based on later-minted PFPs. For experienced players, that may be fair enough, but even so, I know of no basis in copyright law that would support such an outcome absent appropriate language in the transfer agreement.

Potential Solutions

PFP creators who want to transfer copyright in their PFPs to buyers should draft the transfer language carefully. One solution would be to limit the copyright transferred to the specific configuration of traits in each work and exclude any transfer of rights in the traits themselves. Of course, this means that if there is no copyright in automatically assembled works, the buyers receive no copyright.

If the creators retain copyright in the traits, they should consider granting buyers a broad non-exclusive, transferable (with transfer of the PFP only), revocable (automatically upon transfer of the PFP) license to the traits appearing in each PFP, solely for use as incorporated in the associated work. And, in any case, the creators should consider reserving any rights necessary to conduct their business.

Creators should also avoid warranting that they have rights in automatically assembled works and should consider expressly disclaiming any warranty of title.

CC0: PFPs in the Public Domain

Another approach to copyrights in PFPs that has become popular is to release the works directly into the public domain – the so called “CC0” approach. “Nouns”, “mfers”, and “CrypToadz” are all examples of successful CC0 PFPs. The idea seems to be universally available rights will spur viral adoption. I could, for example, use “Noun 1” on packaging for a line of spectacles:

But so could anyone else, at least from a copyright perspective.

The CC0 approach has become so popular that, in an apparent rush to jump on the bandwagon, the creator of “Moonbirds”—one of the most popular and valuable PFPs—announced in August 2022 that it was making all “Moonbirds” public domain, despite originally promising each buyer full commercial rights in their “Moonbird”. Whether the attempt to make “Moonbirds” public domain was effective after making such a promise to buyers remains to be seen.

Trademarks

That is why trademark rights are so important for PFPs. For example, I could obtain exclusive rights to use “Noun 1” on spectacles by being the first to file a trademark application on it, or in first-to-use jurisdictions, by featuring the image as a source identifier on packaging for the spectacles.

I may also have the right to use the word mark “NOUNS” on my goods unless that use would be likely to confuse consumers. At this point, the Nouns creators’ rights to the “NOUNS” mark may not extend far beyond NFTs, which provides an opportunity for enterprising firms to adopt and use the mark on sufficiently unrelated goods and services. To the extent Nouns’ CC0 strategy leads to mass adoption and exposure, such firms would benefit accordingly.

PFP creators who transfer copyright in their PFPs or make them public domain need to consider whether they’d like to take the same laissez-faire approach with trademarks. If not, PFP creators should consider a filing strategy to protect non-NFT goods and services in keeping with their plans, which could of course include use by licensing the mark to third parties. That strategy should consider both the name of the PFP (e.g., “Nouns”) and the works in the PFP, although the PFP creator would have to choose a particular work or works to protect because, at least in the U.S., it’s not possible to file on a “templatized” design (or “phantom mark”) that includes many possibilities.

PFP creators also need to ensure that their trademark and copyright strategies are consistent. For example, if the creator purports to transfer copyright in a particular PFP to a buyer, the PFP creator cannot then expect to use that particular PFP as a trademark.

Conclusion

Attempting to transfer copyright in a PFP to its buyer has its problems. For one thing, there may be no more copyright in a PFP than there is in a monkey selfie. And even if there were, ensuring there’s a written signature for each transfer isn’t easy. Moreover, PFP creators who purport to transfer copyright to buyers without drafting the transfer language carefully may be left without rights in the project’s artwork and may also be exposing themselves to claims from aggrieved PFP buyers. But given the Ninth Circuit’s holding in the monkey selfie case, there is at least one thing Yuga and other PFP creators don’t have to worry about – PETA bringing suits on behalf of “Bored Apes.”

This article was previously posted at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/ papers.cfm?abstract_id=4116638.

Endnotes

- Brian Frye, Are CryptoPunks Copyrightable? Pepperdine L. Rev. (Feb. 8, 2022), https://ssrn.com/abstract=4029323.

- Due to rights clearance issues, I was unable to include an actual “CryptoPunk.” I created the image myself in an attempt to determine the rarest conceivable “CryptoPunk.”

- See https://boredapeyachtclub.com/#/erms (emphasis added).

- See, g., Your Story, https://yourstory.wtf.

- “Ape #ABCD” doesn’t actually exist. To avoid rights clearance issues, the author paired this invented “Ape” with “Ape #4485,” which entered the public domain by operation of the BAYC terms when the NFT’s owner sent it to an inaccessible “burn ” For a pair of “Apes” that were analogous to this pair for purposes of this argu- ment, see “Ape #6578” and “Ape #7065.”

- Not surprisingly, the first four apes are owned by Yuga’s four

- After the BAYC terms say “you own the underlying Bored Ape, the Art, complete- ly,” they go on to provide personal and commercial licenses to the One might argue that Yuga’s grant of these licenses means there was no intent to transfer copyright, and that “you own . . . the Art, completely” has a meaning analogous to when one purchases a painting (“you own the painting”) but receives no copyright in the underlying work. But that analysis, which is based on 17 U.S.C. § 202, would seem to require that Yuga convey some material object, which they have not. In other words, what is it that the buyer “owns” if not the copyright? Physical space on a server somewhere?