What Happens When a Governor Is Unable to Serve?

5.22.2024

When Andrew Cuomo resigned as governor in August 2021, New York had a constitutional procedure in place to fill that vacancy instantly. Under the constitution, Lieutenant Governor Kathy Hochul became governor. So far, so good. But what if she became incapable of serving? Who would make that determination, and how?

New York is one of a minority of states with no procedure for determining gubernatorial inability. Article V, Section 5 of New York’s constitution provides that “In case the governor is impeached, is absent from the state or is otherwise unable to discharge the powers and duties of the office of governor, the lieutenant governor shall act as governor until the inability shall cease. . . . ” Nothing further is mentioned regarding determining inability. We have been fortunate that the situation has not arisen, but why press our luck? A procedure should be put in place to allow for the governor’s voluntary declaration of inability and to address the more troublesome issue of a governor not acknowledging, or contesting, the inability to function.

These are consequential matters. The governor plays a crucial role in how New York State operates. We have seen that is particularly true in times of emergency. New Yorkers should have a governor that is either duly elected or, if needed to be replaced, selected through a carefully developed process that should instill confidence that the continuity and performance of government will be maintained.

NYSBA’s Committee on the New York State Constitution[1] gave this substantial thought and produced a report with recommendations that was approved by the House of Delegates in January 2023.[2] The report made recommendations regarding several aspects of gubernatorial succession, including absence from the state, the order of succession, the appointment of a lieutenant-governor, and addressed the problem of gubernatorial inability.

The New York Law Revision Commission also has studied inability,[3] as has the Fordham University Rule of Law Clinic[4] and many scholars.[5] Recommendations abound and yet we have no procedure. This article will discuss what the federal governments and many states have done to address gubernatorial inability and then present a proposed approach.

The Federal Model

The federal government and at least 31 states have a means of addressing gubernatorial inability to serve. The federal provision, the 25th Amendment,[6] was prompted by the illnesses of President Eisenhower and the consideration of a scenario where President Kennedy was shot but survived as incapacitated. John Feerick, former dean of Fordham Law School and still an active NYSBA member, was a major drafter of the amendment and wrote an important book on the process and result.[7] Certainly, the United States has had at least two lengthy periods where a president at the least appeared to be severely impaired: James Garfield lingered near death for 79 days after being shot in 1881, and Woodrow Wilson suffered a severe stroke in October 1919 and was in office for the remaining 17 months of his term.

The federal procedure for addressing presidential inability invokes the vice president, the cabinet and Congress. A president can declare a temporary inability to serve, and can also declare that the inability is over. It is not unusual for presidents receiving anesthesia to make this declaration, so that a vice president knows to act in case of emergency.[8]

The complications begin when a president is perceived to be unable to serve but does not acknowledge that. In such a case, which has not happened in the 57 years the amendment has been in place, if the vice president plus a majority of the cabinet (or such other body as Congress may provide) certify that the president is unable to discharge the duties of the office, the vice president takes over. The president can resume the duties upon informing Congress, unless the vice president plus a majority of the cabinet disagree and so inform congressional leaders within four days after the president seeks to resume the office. In such case Congress must convene promptly[9] and if it decides within 21 days, “by two-thirds vote of both Houses,”[10] that the president is unable to serve, the vice president continues to discharge the presidential duties. Otherwise, the president resumes the authority. The procedure takes care to assure that one branch cannot determine what happens. There is an initial invocation of inability by the executive branch, which presumably would be in the best position to identify a problem, and then if the president contests, Congress makes the final determination.[11]

Procedures in Other States

There is no pattern among the states as to who initiates consideration of the governor’s condition. Eight states involve members of the governor’s administration or other gubernatorial appointees.[12] Often, one or more statewide elected officials have the responsibility.[13] Several states involve either the legislature[14] or legislative leaders.[15] In nearly all of those states, the final decision is made by the state’s highest court, so the legislative leaders are not charged with both the initiator and decider roles. A few states involve physicians, the deans of medical schools or the commissioner of mental health as part of the initiator group.[16] A number of states involve some combination of executive and legislative, or executive, legislative and judicial officials, in the first phase.[17] Louisiana and Oklahoma procedures include an initiating group which reports to the legislature, which then votes to send the question to the state Supreme Court.[18]

Twenty of the 31 states rely on the state’s highest court to make the final determination of gubernatorial inability.[19] Eight states leave that decision to the legislature, by supermajority vote,[20] and three states invoke a council of officials (and individuals such as a medical school dean) to make the determination.[21] Several states that leave the decision to their highest court provide explicitly for notice to the governor and a hearing.[22]

Three states do not bifurcate the process. Illinois and South Dakota leave the entire issue to the Supreme Court, with no further guidance as to how the decision should be made.[23] In Tennessee, a majority of commissioners of administrative departments of the executive department both initiate and make the final decision.[24]

A governor whose duties have been removed can petition to resume serving as governor, and generally that decision is left to the body that made the final decision in the first instance.

Since the first inability procedure was established, in Mississippi in 1890,[25] only one state has had to invoke the procedure to replace a governor where the governor did not voluntarily declare a disability. In 2003, the governor of Indiana suffered a stroke. The Indiana Supreme Court immediately found him unable to discharge his powers. He died five days later.[26]

In examining the various approaches, most states involve executive branch officials in initiating the process, as they are probably in the best position to know about the governor’s condition. States frequently include other elected statewide officials, which adds to the credibility of the decision, as these officials have the backing of the state’s electorate. And unlike the federal model, those officials exist and can be called upon. Where the state’s highest court is making the final determination, there is a logic to including state legislative leaders, or even the legislature itself, in making the initial recommendation. Four states include the chief justice in the initiator group, but the highest court is not involved in the final determination.[27]

New York Law Revision Commission Proposal

The New York Law Revision Commission recommended a process for involuntarily declaring inability in the mid-1980s. This approach would have the lieutenant-governor and the four legislative leaders unanimously conclude the governor is unable to serve, to bring the matter before the Court of Appeals. The commission believed this would involve all three branches of government in the determination.[28]

The State Constitution Committee Proposal

The NYSBA State Constitution Committee considered the various models in developing its proposal, which largely tracks the federal model, with significant differences in the initiating phase.[29] The governor can declare an inability to serve and resume the governor’s duties when the disability is over (a procedure similar to the federal and virtually all state models). Should the governor not step aside in the case of a perceived inability, if a majority of a committee on gubernatorial succession – consisting of the lieutenant-governor, attorney general, comptroller and six Senate-confirmed heads of executive agencies to be provided by law – finds the governor unable to serve, the lieutenant-governor would take over. If the governor contests this, then the Legislature would decide, by two-thirds vote of each house, whether the governor is unable to serve. This proposal uses similar timelines and procedures to the federal model.

Initiating Phase

There are several aspects in which the committee proposal differs from both the federal and state models. Two significant differences from the federal approach are the role of the vice president and the use of statewide elected officials. Under the federal model, the vice president must agree to initiate the procedure or it goes nowhere. The committee thought that places too much pressure and responsibility on the lieutenant-governor. For example, for various reasons a lieutenant-governor may be reluctant to try to take over – or be seen as trying to seize the reins – which might influence the lieutenant-governor in starting the process.[30] On the other hand, having the lieutenant-governor as one of several officials to make that decision would take advantage of that inside perspective while distributing the responsibility. The large majority of other states do not give a single official an effective veto over initiating an inability procedure.

The federal model has the vice president and cabinet make the decision. The committee’s proposal includes the state’s agency heads but also includes the two elected statewide officials other than the governor and lieutenant-governor: the attorney general and the comptroller. Involving agency heads means some individuals who work regularly with the governor and have strong loyalty to the governor would be involved, who would be cautious in determining inability. Adding the elected statewide officials provides the added credibility of two individuals who have been chosen by a statewide electorate, and who have the current experience of independently running an executive agency in New York. The resulting committee would have a depth of experience and understanding that can effectively gauge both the governor’s ability to serve and the ramifications of making such a decision.

When comparing the state committee’s approach with the models in other states, most states utilize officials, both elective and appointed, who run executive departments to initiate proceedings. Many have several statewide electeds, including a secretary of state and state auditor, so that comprising a committee mostly or entirely of elected officials becomes a more viable option. The major distinction between the committee proposal and elsewhere, including the Law Revision Commission recommendation, is the legislative branch does not participate in the initial determination, as the Legislature has the final say. phase.

The Law Revision Commission included legislative leaders in its initial phase because New York did not have an equivalent of the federal cabinet to rely on to initiate the finding of inability.[31] While New York, and states generally, do not have the equivalent model of a cabinet that has a high profile and meets regularly with the president, it has heads of executive departments with varied executive and political experience who are confirmed by the state Senate, just as on the federal level. Involving select agency heads, along with the attorney general and comptroller, should result in a capable group to make the initial recommendation to proceed.

One other aspect to be noted is that three states involve either physicians (including the dean of a medical school, who presumably is a physician) to participate in the initiating or even final decision regarding inability. The committee did not think it wise to delegate that function directly to a physician. Physicians may not have the expertise needed to make a particular medical determination, and do not necessarily bring any other government or political experience to what is essentially a political decision. The states generally do not require a medical or psychiatric evaluation of the governor, no matter who is making the decision.[32] The committee recognized the value of medical expertise in recommending that the commissioners of the Department of Health and the Office of Mental Health be among the agency heads who make the determination. Those officials, who generally have medical backgrounds, and the inability committee generally should consult with medical expertise where warranted, to inform their decision-making.

Determination Phase

As noted, most states rely on their highest court for the inability determination. Many of these procedures were in effect before the 25th Amendment, which did not include the courts, was ratified. Having the state’s highest court determine fitness to serve is an understandable route for most states to take. Courts are often called upon to determine facts and make a conclusion. Historically, courts are perceived as an entity independent of the political branches that could bring appropriate detachment to the decision.

The Law Revision Commission recommended that the Court of Appeals be the final arbiter because it wanted the legislative branch involved in the original determination, as there was no state equivalent of the federal cabinet, as noted above. It also wanted to separate this procedure clearly from impeachment, in which the Assembly moves to impeach and the Senate (sitting with the judges of the Court of Appeals) adjudicates.[33] If the Court of Appeals is reluctant to find a governor unable to serve, that would be consistent with a presumption in favor of the incumbent retaining the office.[34]

On the other hand, it is noteworthy that the federal model does not involve the Supreme Court. Leaving the decision to a legislative body acknowledges that the decision is substantially a political one, and one which the Legislature is well positioned to make. The Commission on Presidential Disability, appointed in 1985 to review the 25th Amendment, reasoned (as did Chief Justices Burger and Warren) that it would be best to keep the judicial function “separate” in case the Supreme Court will need to “rule on some application of the 25th Amendment.”[35] Usually the highest state court does not engage in fact-finding, but is called upon to do so in determining gubernatorial inability. Thus, the court would be thrust into an a very contentious political process, making the definitive factual determination as to who governs.

An additional concern is that, during the course of the inability process, issues may arise requiring a court ruling; for example, whether the procedures set forth in constitutional and statutory provisions have been met. To have the court make those determinations and then resolve what is inevitably the political question of whether the governor should be relieved of duties confuses the role of the court. In the end, the process must have credibility with the public, and subjecting the court to these potentially conflicting charges may risk that credibility.

A further issue to consider in assigning the final decision to the state’s highest court is the lack of a definition of “inability.” The terms “unable” and “inability” are not defined in the 25th Amendment nor by states that have established procedures. During the deliberations on the 25th Amendment, “[I]t was reasoned that any attempt to define such terms ran the risk of not including every contingency that could give rise to a presidential inability.”[36] In addition, having a definition might open the language to interpretation at what could be a particular challenging time. Asking a court to make the inability determination without guiderails that definitions provide is a fraught enterprise.

Finally, it could be argued that relying on the state’s highest court reduces the partisan nature of the decision. That argument has gotten weaker in recent times, with partisanship seeming to drive a number of political decisions in states where the highest court is elected. In New York, the Court of Appeals is appointed by the governor through a merit selection process.[37] While this approach is clearly superior to highly financed elections, when decisions are being made that have a direct impact on the governor, particularly whether the governor can retain office, there will be concerns that the court may lack full objectivity in making its determination.[38]

Having the Legislature make the final decision, by two-thirds vote, after referral by executive branch officials, seems to strike the correct balance, with the supermajority requirement assuring that the decision to replace the governor, even temporarily, would be a substantial hurdle, as is appropriate when determining that the individual selected to be the chief executive is not fit for that role. Leaving the decision to the political branches means political considerations will be involved. But the framers of the 25th Amendment saw this as well. Removing a governor, no matter the reason, is a political decision, and maybe even a partisan decision. Political considerations can cut many ways, from power grabs to risking the voters’ bile when acting too rashly. Given how rarely the inability mechanism has been used, and the safeguards built into the process, the committee felt leaving the decision-making to the executive and legislative branches and preserving the judicial role for the courts in this process most effectively serves New Yorkers.

Conclusion

New York is one of a minority of states that do not have procedures in place in the event the governor is found unable to serve. Several legal organizations, including the New York State Bar Association, and many scholars have come forward with plans to address this lack of preparedness, and one suggestion, by NYSBA’s Committee on the New York State Constitution, seems viable – namely, that New York should largely follow the federal plan for succession, but with some tweaks, or customized provisions, that address the state’s specific requirements for a transfer of power, most notably in the initiating phase when the governor’s capacity to serve is being assessed. Of course, any gubernatorial plan would necessarily involve the lieutenant governor, and there are proposals afloat to deal with those succession issues.

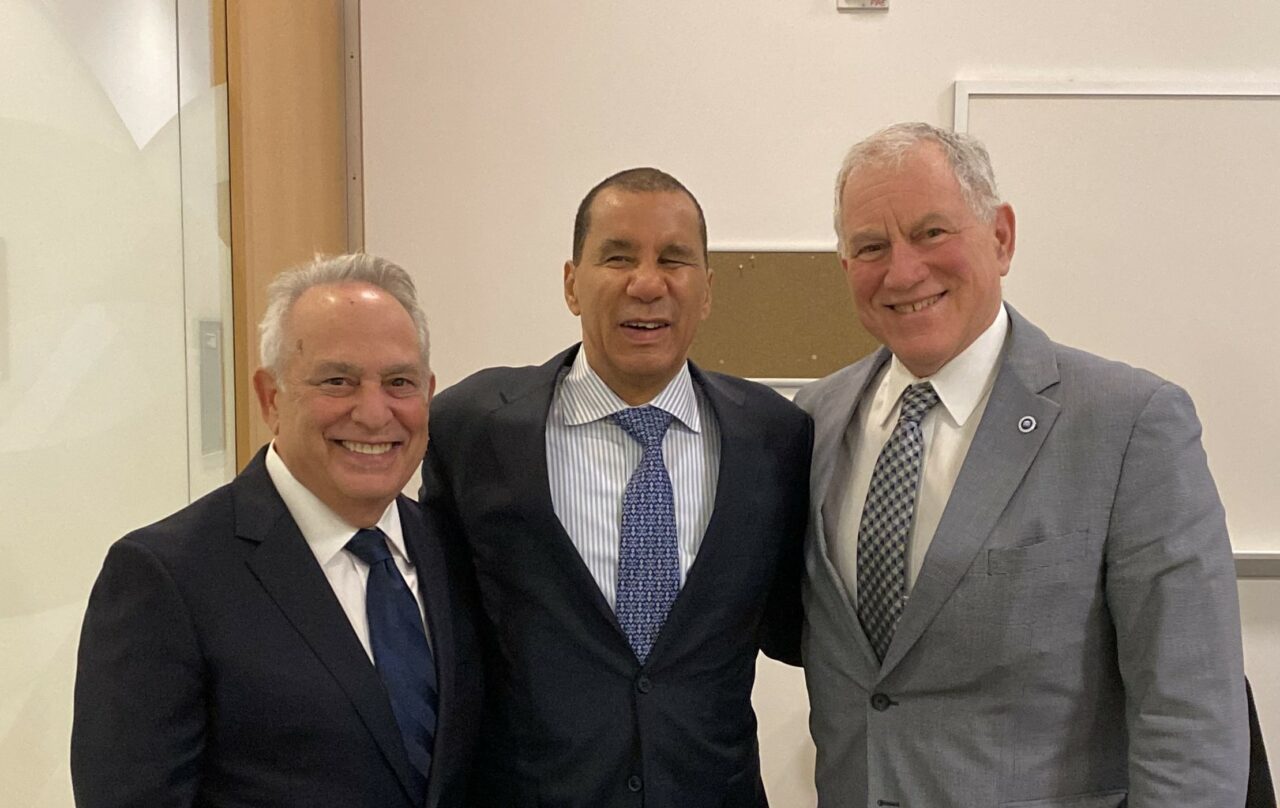

Alan Rothstein is the chair of the Subcommittee on Gubernatorial Succession, NYSBA Committee on the New York State Constitution. Prior to his retirement, he was general counsel of the New York City Bar Association.

[1] Hereinafter “State Constitution Committee.”

[2] Report and Recommendation of the New York State Bar Association Committee on the New York State Constitution: Constitutional and Statutory Recommendations Regarding Gubernatorial Succession and Inability, adopted by the House of Delegates on January 20, 2023 (hereinafter “Gubernatorial Succession Report”), at https://nysba.org/app/uploads/2022/06/final-Report-on-Gubernatorial-Succession-NYSBA-Committee-on-the-NYS-Constitution-January-2023.pdf.

[3] NY Law Revision Commission, Report Relating to Gubernatorial Inability and Succession, Absence from the State and Filling a Vacancy in the Office of Lieutenant Governor (Senate No. 8365, Assembly No. 10454 (1986) (hereinafter “1986 Law Revision Commission Report”).

[4] Fordham Law School Rule of Law Clinic (Ian Bollag-Miller, Stevenson Jean, Maryam Sheikh & Frank Tamberino), Changing Hands: Recommendations to Improve New York’s System of Gubernatorial Succession (June 2022) (hereinafter “Fordham Rule of Law Clinic”).

[5] See, e.g., Michael J. Hutter, “Who’s in Charge”? Proposals to Clarify Gubernatorial Inability to Govern and Succession, 12 Gov’t & Pol’y J. 1 (2010) (C:/Users/rothh/Downloads/SSRN-id1645381%20(2).pdf); William E. Raftery, Gubernatorial Removal and State Supreme Courts, 11 J. App. Prac. & Process 165 (2010) (hereinafter “Raftery”) (https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1269&context=appellatepracticeprocess); Calvin Bellamy: Presidential Disability: The Twenty-Fifth Amendment Still an Untried Tool, 9 B.U. Pub. Int. L.J. 373 (2000) (https://www.bu.edu/pilj/files/2024/04/Bellamy.pdf).

[6] The text of the 25th Amendment can be found at https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/essay/amdt25-1/ALDE_00001013/#:~:text=1%20Overview%20of%20Twenty%2DFifth%20Amendment%2C%20Presidential%20Vacancy,-Twenty%2DFifth%20Amendment&text=Section%201%3A,Vice%20President%20shall%20become%20President.

[7] John D. Feerick, The Twenty-Fifth Amendment: Its Complete History and Applications, Third Edition (2014) (hereinafter “Feerick”).

[8] The 25th Amendment also sets forth a procedure for appointing a vice president should the elected vice president have to assume the presidency, as did Gerald Ford in 1974.

[9] If Congress is not in session, it must assemble within 48 hours and decide within 21 days after it is required to assemble.

[10] This provision “is designed to make clear that each House votes separately on a nomination. . . . ” Feerick, supra note 7, at 111.

[11] Id. at 82.

[12] Cal. Const., art. V; § 10; Conn. Const., art. IV, § 18; Del. Const., art. III, § 20; Iowa Const. art. IV, section IV, § 7.14; Minn. Stat. 4.06; Okla. Stat. § 74-8; Ore. Rev. Stat. §§ 176.303, 176.312; Tenn, Const., art. III, § 12.

[13] See, e.g., Ala. Const., art. V, §§ 127-8; Geo. Const., art. V, § 4; Ill. Iowa Stat. § 7.14; Ken. Const., art. 6, § 84; La. Const., art. IV, § 14; Maine Const., art. V-1, § 15; Miss Const., Art V, § 131; NH Const., Executive Power, § 49(a); SC Const., art. IV, § 12; Vir. Const., art. V, § 16.

[14] Col. Const., art. IV, § 13(6); La. Const., art. IV, § 14; Mar. Const., art. II, § 6-7; NJ Const., art. V, § 8; NC Const. art. III, § 3; Ohio Const., art. III; § 22; Okla. Stat. § 74-8.

[15] Cal. Const., art. V; § 10; Ind. Const., art. V, § 10; Vir. Const., art. V, § 16; Ore. Rev. Stat. §§176.303, 176.312.

[16] Del. Const., art. III, § 20; Iowa Const. art. IV, section IV, § 7.14; Ore. Rev. Stat. §§ 176.303, 176.312.

[17] See, e.g., La. Const., art. IV, § 18; NJ Const., art. V, § 1, ¶ 8; Mo. Const. art. IV, §11(b); NC Const., art. III, § 3.

[18] La. Const., art. IV, § 14; Okla. Stat. § 74-8.

[19] All rely on a majority vote of the justices except Kentucky, which requires a unanimous vote. Ala. Const., art. V, §§ 127-8; Cal. Const., art. V, § 10; Col. Const., art. IV, § 13(6); Fla. Const., art. IV, § 3; Geo. Const., art. V, § 4; Ill. Const., art. V, § 6; Ind. Const., art. V, § 10; Ken. Const., art. 6, § 84; La. Const., art. IV, § 18; Maine Const., art. V-1, § 15; Mar. Const., art. II, §§ 6-7; Mich. Const., art. V, § 26; Miss Const., Art V, § 131; Mo. Const. art. IV, §11(b); NH Const., Executive Power, § 49(a); NJ Const., art. V, § 1, ¶ 8; Ohio Const., art. III, § 22; Okla. Stat. § 74-8; SD Const., art. IV, § 6; Utah Const., art. VII, § 11(6).

[20] Conn. Const., art. IV, § 18; Del. Const., art. III, § 20; Mass. Const., art. XCI; Minn. Stat. 4.06; Mont. Const., art. IV, § 14; NC Const., art. III, § 3; SC Const., art. IV, § 12; Vir. Const., art. V, § 16.

[21] Iowa Stat. § 7.14; Ore. Rev. Stat. §§ 176.303, 176.312; Tenn, Const., art. III, § 12.

[22] See, e.g., La. Const., art. IV, § 14; La. Const., art. IV, § 14; NJ Const., art. V, § 1, ¶ 8; NC Const., art. III, § 3.

[23] Ill. Const., art. V, § 6; Okla. Stat. § 74-8.

[24] Ten. Const., art. III, § 12.

[25] Raftery, supra note 5, at 170.

[26] Id. at 175.

[27] Conn. Const., art. IV, § 18; Del. Const., art. III, § 20; Mass. Const., art. XCI (the chief justice plus a majority of the associate justices initiate the inability proceeding); Minn. Stat. 4.06. In Iowa and Oregon, the chief judge is involved in the panel that makes the final inability determination. Iowa Const. art. IV, section IV, § 7.14; Ore. Rev. Stat. § § 176.303, 176.312.

[28] NY Law Revision Commission Report, supra note 3, at 4-10.

[29] The discussion of inability in the Gubernatorial Succession Report (supra note 2) may be found at 20-23 and includes additional details about the recommended process.

[30] Raftery, supra note 5, at 168.

[31] NY Law Revision Commission, Recommendations of the Law Revision Commission to the 1986 Legislature (1986), 4-6.

[32] Georgia requires testimony of at least three physicians including one psychiatrist at a court hearing on gubernatorial inability. Geo. Const., art. V, § IV.

[33] Id. at 9-10.

[34] Fordham Rule of Law Clinic, supra note 4, at 7.

[35] The commission, appointed by the White Burkett Miller Center for Public Affairs at the University of Virginia, included Chief Justice Burger. Chief Justice Warren also believed the Supreme Court should not be included in the disability process. Feerick, supra note 7, at 221-3 (quoting White Burkett Miller Center, Report on Presidential Disability and the Twenty-Fifth Amendment (Kenneth W. Thompson, ed. 1988).

[36] Feerick, supra note 7, at 178.

[37] N.Y. Constitution, Art. VI, Section 2.

[38] The concerns may be allayed, but only to an extent, by insulating the court from the initial phase of the inability process. See Fordham Law School Rule of Law Clinic report, supra note 4, at 7.

[39] Consideration of inability leads to other gubernatorial succession topics. They include:

- How to select a lieutenant-governor when the sitting lieutenant-governor becomes governor;

- What should the appropriate line of succession be to the governorship;

- In the digital/internet age, should there be a provision, as in New York and elsewhere, that the lieutenant-governor acts as governor when the governor is “absent from the state.”

The State Constitution Committee addressed these issues in its report, in an attempt to set forth a structure to fully address who should take over as governor when the need arises, and how and when. I commend that you read the report, which will provide a sense of the concerns and complexities that are involved.